Morocco: Pages of a Living Tradition | Pt. IV

Mufti Hussain Kamani

This is part IV of a travelogue series. Click to read part I, part II, and part III.

Part IV: Chefchaouen

Wednesday: Arrival in Chefchaouen

We departed Rabat early Wednesday morning right after breakfast for a five-hour drive through the winding roads of the Rif Mountains. To be honest, this was the one stop on our Morocco trip that I wasn’t too excited about. Chefchaouen’s reputation, in my mind, had been shaped mostly by social media: photo after photo of blue alleyways, travel influencers urging people to visit. Unlike Fes or Marrakesh, I hadn’t come across many classical references to this city in scholarly works. It seemed more like a place known for its visuals than its significance. But as the journey unfolded, my perspective began to shift.

On the bus, we spent our time reading from al-Shifāʾ of Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ. We covered chapters on the Prophet’s ﷺ loyalty, humility, justice, and dignity. After class, many of the attendees rested. Mufti Muntasir and I conversed for much of the ride, covering topics ranging from seminary curriculum development to the dangers of scholarly arrogance.

When we arrived in Chefchaouen, the bus dropped us off at the base of the mountain. From there we walked up through the old city, full of the narrow, winding alleyways painted in shades of blue. That evening, we gathered again for a short class in one of the hotel’s halls.

One thing that stood out was the cultural tone of the city. While much of Morocco has an obvious French colonial legacy, Chefchaouen had a stronger Spanish influence. Many signs in the city were trilingual (Arabic, French, and Spanish).

The rest of the day was unstructured. Some attendees explored the town, while others found quiet spots to sit, reflect, and take in the mountain air.

The Color Blue

Chefchaouen was the second “blue city” I had heard of. The first was Jodhpur, India. Located in the Indian state of Rajasthan, Jodhpur is often referred to as the “Blue City” due to the distinctive indigo-washed houses clustered around the towering Mehrangarh Fort. The origin of this color is debated. Some trace it back to Brahmin households, who allegedly painted their homes blue to denote their caste and ritual purity. Others suggest more practical explanations: the color deters mosquitoes or helps reflect sunlight, cooling the interior of the homes. What began as a localized practice around the 15th century eventually spread across Jodhpur’s old city, creating the surreal landscape that the city is now known for.

Jodhpur, India | Photo by Abhinav Tripathi on Unsplash

Half a world away, in the Rif Mountains of northern Morocco, Chefchaouen has a similar visual mystique. Though it was founded as a mountain stronghold against Portuguese incursions, the famous blue did not appear until centuries later, most likely in the 1930s or 1940s.

Why the city turned blue is still debated. One explanation points to the arrival of Jewish refugees, some fleeing European fascism, others tracing their roots to earlier waves from al-Andalus. In Jewish tradition, the color blue has religious significance, particularly tekhelet: a dye used for religious garments and paraphernalia. Others believe the reasons were more practical, as mentioned above.

Chefchaouen, Morocco

Chefchaouen, Morocco

Fortress of the North

Though it is now a peaceful and charming vacation spot, Chefchaouen was not founded as a retreat. It was a ribāṭ (military frontier post) before it was a refuge. The name of the city (pronounced shafshāwun) alludes to its geography. According to several Arabic sources, the name comes from the Berber “shuf shawen”, meaning “look at the mountain peaks.”

Chefchaouen was established in 1471 by Moulay ʿAlī b. Mūsā b. Rāshid, a descendant of the Prophet ﷺ and celebrated warrior. His goal wasn’t leisure or trade, but defense: to guard the Muslim frontiers from Christian invasions pressing in from the northern coast. As one historical account records:

بناها بنو راشد من شرفاء العلم، وكانوا أهل جهاد ومرابطة على العدو ببلاد غمارة والهبط.[1]

[The city] was built by Banū Rāshid, noble people of knowledge. They were people of jihād and stationed defense along the frontlines in the lands of Ghumārah and al-Hubṭ.

The city’s foundation was deeply tied to its strategic location and abundant water. Our guide noted that the main reason people settled here was the flowing mountain water, which is still channeled through narrow canals throughout the city today.

After the death of Moulay ʿAlī, Chefchaouen remained under the rule of his descendants. For decades, they governed through alternating periods of peace and conflict. By the mid-16th century, their independence was brought to an end by the expanding Saʿdī Dynasty, who laid siege to the city. At the time, Chefchaouen was under the command of al-Amīr Abū ʿAbd-Allāh Muḥammad, son of the city’s founder. With the siege tightening and no reinforcements in sight, the Amīr made a fateful decision.

On the night of Friday, 2nd of Ṣafar, 969 AH, the prince, his family, and close companions escaped through the mountain that towers over the city. They descended toward the coastal port of Targa near Tetouan, and a week later they boarded a ship to the Hijaz. Their final destination was al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah. There, in the illuminated city of the Prophet ﷺ, the last amīr of Banū Rāshid settled, passed away, and was buried.[2]

From Fortress to Fountain of Knowledge

Though it experienced political upheaval, Chefchaouen became a center of scholarly life. It produced fuqahāʾ, grammarians, genealogists, and preachers, many of whom traveled to study in Fes but then returned here to teach their community.

Al-Ziriklī’s encyclopedic work al-Aʿlām mentions some of these scholars: among them was Aḥmad al-Sharīf (971–1027 AH / 1564–1618 CE), a descendant of the great saint ʿAbd al-Salām b. Mashīsh. He was a Mālikī faqīh, genealogist, and expert in legal documentation. Though he reluctantly accepted a position as qāḍī in Chefchaouen, he later withdrew from the position and dedicated himself to teaching. His works include:

A ḥāshiyah on Sharḥ al-Ṣughrā

A risālah on the ancestry of the Banū ʿAbd al-Salām ibn Mashīsh

Collected sayings of his teacher Abū al-Maḥāsin

Another native scholar was Muḥammad al-Shafshāwunī (1179–1232 AH / 1766–1817 CE), a Mālikī faqīh and grammarian. Though he spent much of his career in Fes, his origins were here in Chefchaouen. His scholarly legacy includes glosses on al-Muḥallā, al-Kharshī, and Talkhīṣ al-Miftāḥ in rhetoric.

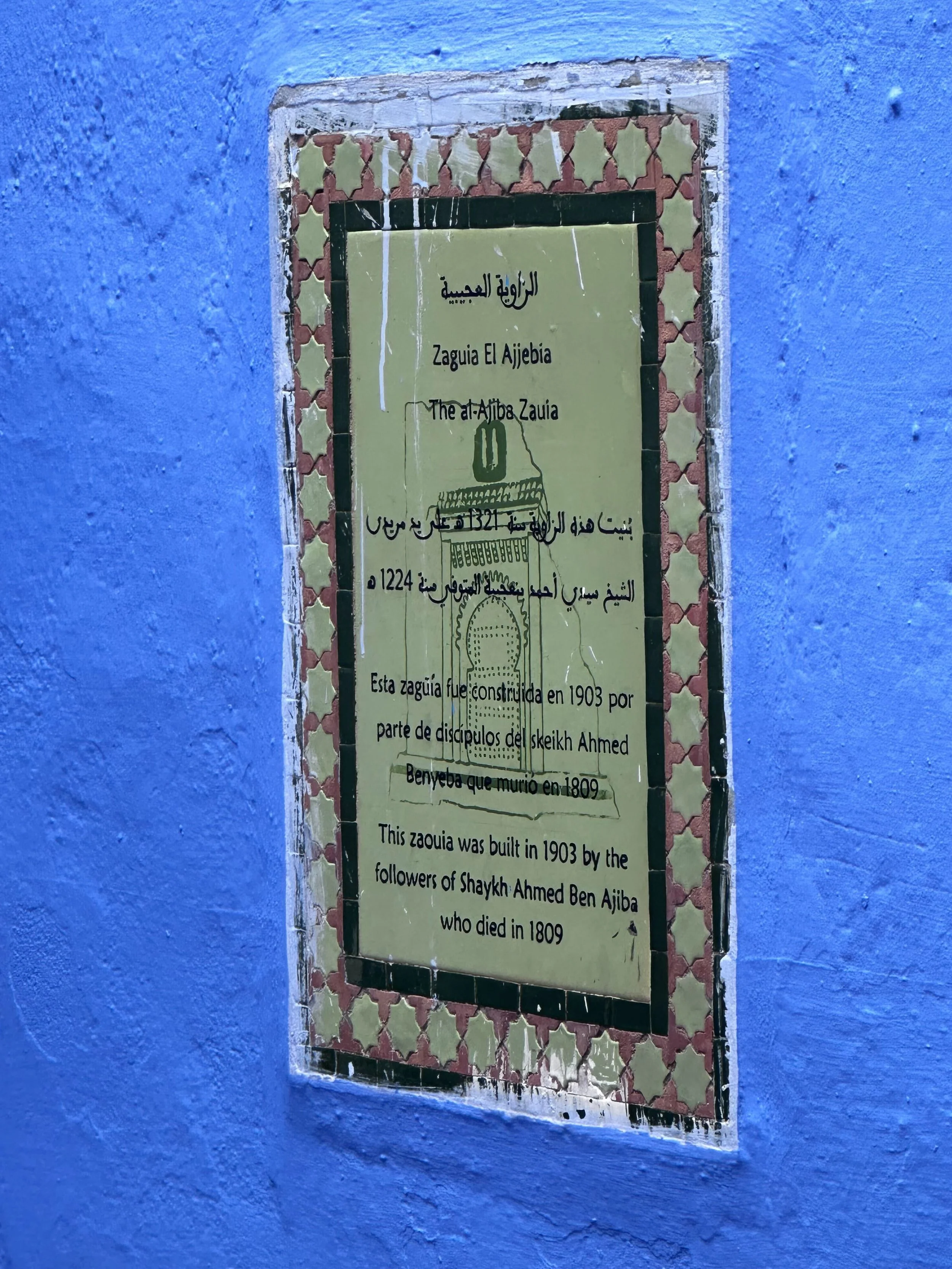

al-Zāwiyah al-ʿAjībiyyah, built by the followers of Shaykh Aḥmad ibn ʿAjība

The spiritual and academic legacy of Chefchaouen may not be as widely cited as Fes or Marrakesh, but it is embedded in its zāwiyahs, its twelve mosques, and the tombs of its awliyāʾ. One poet expressed his love for the city in the following lines[3]:

شفشاون يا شفاء النفس من نصب … ومن عنا وشفاء الروح من وصب

O Chefchaouen, healer of the soul from fatigue and affliction and cure for the weary spirit.

مسقط رأسي وأنسي مع جهابذة … أَربوا على كل ذي علم وذي أدب

My birthplace and my solace, home to giants who surpassed all in knowledge and refinement.

زدت جمالاً على حمراء أندلس … وفقت بيضاء غرب منتهى الأدب

You surpassed the Alhambra of Andalus in beauty, and outshone Casablanca in grace.

ماء معين وأشجار منوعة … تعجز عن وصفها الأقلام في الكتب

With flowing waters and trees of all kinds, pens cannot capture it in books.

Thursday: Walking Through the Blue City

The next morning after breakfast, we set off for our walking tour of Chefchaouen. We began at 9:30 AM and walked up and down through the winding alleys and sloped paths of the city until 12:30 PM. The weather was perfect: the sky was mostly clear and occasionally gave way to a gentle, brief rain.

Waiting for us outside the hotel was our tour guide, who introduced himself as ʿAbd al-Salām al-Jaddāwī. Despite his elderly appearance, he possessed remarkable strength and energy. As we traversed the city’s terrain, he never tired and kept pace steadily.

ʿAbd al-Salām spoke multiple languages fluently. His Arabic was very eloquent. He also spoke Tamazight, Spanish, German, French, and English. Throughout the tour, he was incredibly detailed, recalling precise dates, events, and historical anecdotes from the city’s rich past.

About a third of the way through the walk, he casually shared with us his age: he was 83 years old. He started to reminisce and tell us about his childhood. At this advanced age, he still opens the oldest zāwiyah in the city every morning. He sits there alone for two and a half hours, reciting Quran and engaging in dhikr.

He mentioned that in the 1950s, groups from Chefchaouen would travel to Fes to visit Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī, a major figure of Islamic scholarship in the modern era. Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy was a reviver of the tradition of traveling for hadith transmission. He sought out high-level chains (ʿuluww al-asānīd) and preserved the legacy of short sanad connections to the Prophet ﷺ. Historically, it was through people like him that the shortest chains of transmission were maintained and passed on.

Although ʿAbd al-Salām is not a formally trained scholar, he had heard hadith directly from Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy. He was born in 1943 in Chefchaouen, just down the street from the madrasah where he memorized the Quran as a child. His childhood home still exists today. As a teenager, ʿAbd al-Salām made the journey to visit Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy, where he sat in his gatherings, studied under him briefly, and heard hadith from him twice in total. Mufti Muntasir asked him detailed questions about the years, locations, and dates of these encounters, cross-referencing them with what he knew of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy’s final years. Everything lined up. It was authentic. ʿAbd al-Salām had met Shaykh Abdul Hayy al-Kattani near the end of the Shaykh’s life and received from him direct transmission of Hadith.

When we learned that he had heard from Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ḥayy, Mufti Muntasir and I requested an ijāzah in hadith from him. For the average observer, requesting an ijāzah from someone who isn’t a scholar might seem odd. But those familiar with the science of hadith know that the practice of traveling for shorter chains of transmission is a long-established tradition. When senior scholars would visit cities and narrate hadith to large gatherings, everyone present would have their names recorded and receive ijāzah, whether or not they were formal ṭullāb al-ʿilm. Parents would bring their young children so they could attain the barakah of being connected to the Prophet ﷺ through a narrator that would likely pass away by the time the child grew up to be an adult. This was not only acceptable, but a cherished practice.

A stunning example of this is Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad b. Abī Ṭālib al-Ḥajjār. Known as Ibn al-Shiḥnah, he wasn’t recognized as a scholar for most of his life. He worked as muqaddam al-ḥajjārīn (foreman of the stonecutters) in Damascus for over 25 years. However, as a child in 630 AH, he had attended a reading of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī with the great al-Zabīdī atop Mount Qāsiyūn. His attendance remained unknown until a century later in 730 AH, when his name was rediscovered in old records from hadith gatherings (ṭabaqat al-samāʿ).

From that moment, scholars from all over the Muslim world flocked to receive hadith from him through his incredibly short chain. Even the Sultan al-Malik al-Nāṣir attended his gatherings and honored him. Despite not being a scholar, he became one of the most sought-after transmitters of his time. His final years were devoted to serving this noble tradition, and his funeral was attended by multitudes.[4]

This demonstrates how attending even a single gathering where the noble sunnah is being transmitted can become a bridge of light that connects multiple generations to the Prophet ﷺ. Among those present in our group that day was a family I’ve known for years: Fahad and Aiman, who is currently a student at the Qalam Seminary, along with their four-year-old daughter Afiyah Chaus. Fahad and I have known each other for over twenty years. That Thursday morning, their young daughter Afiyah received ijāzah in hadith from ʿAbd al-Salām.

Afiyah meeting ʿAbd al-Salām

Because of the nearly 80-year age gap between Afiyah and ʿAbd al-Salām, it’s possible that she now possesses one of the shortest isnād chains of her generation. Parents, teachers, and — most importantly — tawfīq from Allah facilitate the shortest chains. It’s not something one can acquire through their own efforts. Afiyah’s presence at that moment, with the support of her parents and Allah’s will, marked the continuation of that sacred tradition. May Allah keep her firm on the dīn, and make her a scholar and transmitter of hadith.

We then recited the ḥadīth al-musalsal bil-awwaliyyah to him, and he responded by reciting the hadith on “أفشوا السلام” to us. This exchange sealed our sanad and gave us all a link to the noble Prophet ﷺ, through a man who heard from one of the last great muḥaddithūn of our age.

As the tour came to a close, ʿAbd al-Salām walked us all the way to the edge of the city, right up to our bus. He shook our hands, made duʿāʾ for us, and asked us to enjoy the rest of our trip.

This encounter was completely unexpected: a divine gift, not just for Mufti Muntasir and me, but for every attendee of the Qalam Hadith Tour. A brief walk through the blue city became a luminous link to the light of prophethood.

وصلى الله على سيدنا وحبيبنا محمد وعلى آله وصحبه وسلم تسليما كثيرا

Notes:

[1] Aḥmad b. Khālid al-Nāṣirī, al-Istiqsā li-akhbār duwal al-maghrib al-aqṣā (Casablanca: Dār al-Kitāb), 5:41.

[2] al-Nāṣirī, al-Istiqsā, 5:41.

[3] Ibn Zaydān al-Sijilmāsī, Itḥāf aʿlām al-nās bi-jamāl akhbār ḥāḍirah maknās (Cairo: Maktabah al-Thaqāfah al-Dīniyyah, 2008), 5:566.

[4] Ibn Kathīr, al-Bidāyah wal-Nihāyah (Cairo: Maṭbaʿah al-Saʿādah), 14:150.

Mufti Hussain Kamani is the Director of the Qalam Seminary and a senior faculty member, where he teaches hadith, fiqh, and tazkiyah. With over two decades of experience in teaching and community leadership, he has mentored and trained over a thousand students, many of whom now serve as imams, chaplains, educators, and leaders across the United States.