Morocco: Pages of a Living Tradition | Pt. I

Mufti Hussain Kamani

Part I: Casablanca & Marrakesh

Introduction

An Egyptian poet wrote regarding Morocco:

بلد شروق، يفطرُ على الكرم، ويتغذى على المعرفة، وينامُ على الحبِّ

“A land of sunrises, which breaks its fast on generosity, is nourished by knowledge, and rests upon devotion.”

We landed in Casablanca at 9:00am after a seven-hour flight from Dulles. The international airport lies about 19 miles outside the city. It was quiet and mostly empty, and the staff handled everything with a sense of calm. This was my first time ever setting foot in Morocco. For years, I had studied its scholars, admired its legal minds, read the words of its spiritual masters, and imagined its landscapes. In class, I would often ask students from Morocco to tell us about the food, culture, and history. We frequently referred to the scholars of this region while explaining narrations and exploring legal issues, especially those tied to the Mālikī school. I had long hoped that one day I would walk its streets and witness the tradition that had shaped so much of our shared Islamic heritage. By the faḍl of Allah, that hope was realized in the summer of 1447 AH/2025 CE, on the annual Morocco Hadith Tour organized by Qalam. With every passing hour after we landed, it got hotter. The sky was clear, the sun bright, and the temperature rose with no signs of stopping.

History

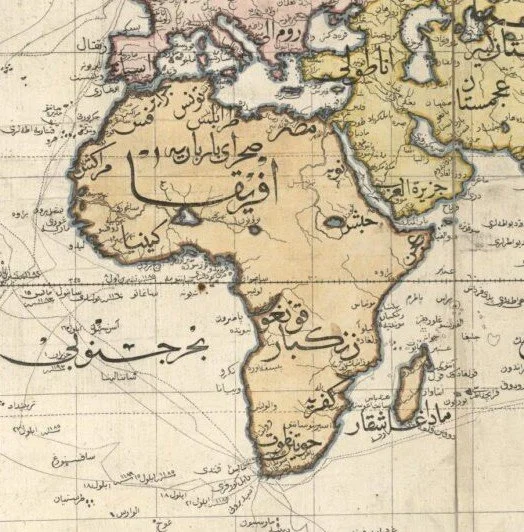

The modern nation-state of Morocco was historically part of a broader region known as the maghrib (“the West”), or al-maghrib al-aqṣā (“the furthest West”). Today we often refer to this region as al-maghrib al-ʿarabī (the Arab West) or shamāl ifrīqiyah (North Africa). The Muslim conquest of this region can be said to have begun under the caliphate of Sayyiduna ʿUmar (RA) and the military leadership of ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ (RA), who conquered Barqa (Cyrenaica) and Tripoli in what is now Libya in 22 AH.[1] Some entry was made into ifrīqiyah under the caliphate of Sayyiduna ʿUthmān (ra), but major raids into North Africa were not conducted until later towards the end of the 7th century CE. The Muslim armies faced both the Byzantines who ruled the northernmost part of the continent, as well as native tribal leaders who staunchly resisted conquest. In the 8th century CE, large numbers of nomadic tribes embraced Islam, making North Africa possibly “the most Islamized of the conquered areas by that time.”[2] Soon thereafter, the maghrib served as a launching pad for the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Today, North Africa is divided by postcolonial borders into multiple nation-states. Though Morocco shares many cultural and linguistic features with the broader region, it also has a distinct identity and history, which we had an opportunity to witness on this trip. Throughout my travels, I made it a point to document the experience and read what our ʿulamāʾ have written about the cities, scholars, and awliyāʾ we visited. I pray that this series of travelogues serves as a window into this blessed corner of the Muslim ummah.

Arrival in Casablanca

Written aboard the train to Marrakesh

From the airport, we caught a local train to the city. The ride took about 40 minutes and cost roughly $5 USD. It was a smooth journey. I hadn’t slept on the flight; I was too caught up reading نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق (The Delight of One Who Longs to Traverse the Horizons) by the 6th-century geographer al-Sharīf al-Idrīsī. The excitement of finally setting foot in Morocco and the substance of the book fed into each other. It didn’t feel right to close my eyes.

Through the windows, Casablanca began to take form. Quiet roads, light-toned buildings, square apartment blocks, palms and olive trees dotted the landscape. It felt familiar in an unexpected way.

The Spanish name Casablanca comes from “casa” meaning house and “blanca” meaning white, directly translated into Arabic as al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ (الدار البيضاء). The name likely traces back to a cluster of pale structures that once faced the Atlantic. What struck me is that even today, the buildings are still pale-colored and aptly reflect the name of the city.

Historically, this area was called Anfa, a port city inhabited by the native Amazigh (Berbers) of the region. Some of the locals I spoke to mentioned that they prefer to be called ‘Amazigh’ (pl. Imazighen) – which means ‘free people’ in their native language, Tamazight – rather than ‘Berber’ (بَرْبَر), since the latter is seen as a pejorative that shares a root with the word ‘barbarian’ (though the etymology of the word is disputed). It is important to note that classical Muslim scholars have used بَرْبَر as a neutral term to refer to the Amazigh and other ethnic groups native to North Africa, without any negative connotation. Nonetheless, this is not the preferred usage of the Amazigh themselves.

Al-Idrīsī mentions a historical account regarding how the Amazigh/Berbers came to North Africa:

“وكان ملكهم جالوت بن ضريس بن جانا… فلما قتل داود عليه السلام جالوت البربري رحلت البربر إلى المغرب حتى انتهوا إلى أقصى المغرب فتفرقت هناك…”[3]

“Their king was Jālūt b. Durays b. Jānā… After Dāwūd (AS) killed Jalut, the Berbers departed towards the Maghreb until they reached the far west, where they settled and dispersed.”

Though the veracity of the above account is debatable, it alludes to how long the Amazigh have inhabited the maghrib. Morocco was colonized by the French in 1912, which transformed Casablanca into a colonial capital. Infrastructure expanded, but so did inequality. Independence wasn’t won easily; over 300,000 Moroccans are estimated to have died in the resistance that led to liberation in 1956, raḥimahum Allāhu taʿālā.

We boarded the train towards Casa Voyageurs, Casablanca’s main train station, where we were meant to transfer onto the train to Marrakesh. The station had a small masjid quietly tucked beside it, and it was well-kept. People lined up calmly with a kind of public courtesy that felt natural. Only a few skipped ahead and no one made a scene.

We boarded the train to Marrakesh next. As the city faded, the land changed. First came flat farmland, covered in dry and golden crops: wheat, barley, sunflowers, essentially the type of crops that don’t ask much of the earth. Then came the red-orange desert, stretching toward distant mountains. The buildings disappeared and there was only a natural landscape as far as the eye could see.

Halfway into the journey, a group of conductors came to check tickets. It turned out that ours were valid for Marrakesh but not for this specific train, since we had mistakenly transferred at the L’Oasis train station, one stop before Casa Voyageurs. I tensed, expecting a reprimand or fine. But the lead conductor just smiled and gently told us to be more careful next time, then moved on. It reminded me of the Prophet’s ﷺ statement:

“الرِّفْقُ لا يَكُونُ في شيءٍ إلَّا زَانَهُ، ولا يُنْزَعُ من شيءٍ إلَّا شَانَهُ.”

“Gentleness is not found in anything except that it beautifies it, and it is not removed from anything except that it makes it deficient.” (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, kitāb al-birr wal-ṣilah wal-ādāb)

The ride from Casablanca to Marrakesh is just under three hours. In that short time, I had already felt a shift in the terrain, architecture, and even the rhythm of life between the two cities.

A verse of the Quran came to mind:

قُلْ سِيرُوا فِي الْأَرْضِ فَانظُرُوا…

“Say: travel through the land and observe…” (6:11)

Our scholars generally discourage prolonged traveling (i.e. for several years) purely for leisure and tourism, classically referred to as siyāḥah. In contrast, they greatly encourage traveling for sacred knowledge, to fulfill the rights of others, to visit righteous people, and to reflect on the creation of Allah. Witnessing the changing landscape from the train brought to mind the transient nature of this dunyā, and the folly of one who obsesses over leaving his ‘legacy’ in such an evanescent place. Allah relates to us the stories of past nations for many reasons, among them to remind us that only that which He decrees will remain.

Marrakesh

…ومدينة مراكش اليوم من أعظم مدن الدنيا بهجة وجمالا بما زاد فيها الخليفة الإمام وخليفته أمير المؤمنين أبو يعقوب وخليفتهما أبو يوسف رضي الله عنهم

The city of Marrakesh today is one of the most delightful and beautiful cities in the world due to the additions made by the Caliph al-Imam, his successor the Amīr al-Muʾminīn Abu Yaqub, and their successor Abu Yusuf, may Allah be pleased with them…

– Kitāb al-Istibṣār Fī ʿAjāʾib al-Amṣār, by an unknown author from the 7th century A.H.

We arrived in Marrakesh at 2:30 PM on Wednesday and walked into the beautiful, large train terminal. It felt as though we’d stepped into a bustling market. As we exited, taxi drivers immediately began calling us toward them. One particular driver picked us up and we began weaving through the busy city.

We drove through crowded roads, full of tourists and locals carrying on with their day. As we neared the city walls and entered through Bāb Agnau — one of Marrakesh’s 19 gates — the city transformed. We passed through tight alleyways filled with vendors, families, and travelers from across the globe. Eventually, our driver dropped us off at the furthest point he could reach by car. The rest of the journey had to be done on foot.

An older man with a cart (what I believe is called a qūlī locally, or more commonly in Arabic referred to as ḥammāl) helped us from there. He placed our luggage in his cart and led us through another 5-7 minutes of winding paths. As we entered the square near our riyāḍ (a traditional Moroccan guesthouse built around a central courtyard, often with a garden or fountain), juice stalls lined both sides, offering orange, dragonfruit, pineapple, lemon and other local fruits that I didn't recognize. Children played nearby, while others browsed souvenir shops and food stalls.

We finally arrived at our riyāḍ, checked in, and were welcomed with something I had been quietly anticipating for days: a hot glass of Moroccan tea served in the most traditional way. There was something about drinking it here in Morocco that made it perfect.

City of Gardens

Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd-Malik al-Awsī (d. 703/1303), a former qāḍī of Marrakesh, wrote about his beloved city:

للهِ مراكشَ الغرَّاءَ منْ بلَدٍ

وحبَّذَا أهلها السادَات منْ سكنِ

إنْ حلها نازِحُ الأوْطانِ مغتَرِب

أسلَوْه بالأنْسِ عنْ أهْلٍ وعنْ وطَنِ

بيْن الحدِيثِ بها أوِ العيَانِ لها

ينْشَأُ التّحاسُدُ بيْنَ العَيْنِ والأُذُنِ

By Allah, how splendid is Marrakesh, that noble land!

And how blessed are its people, the honored who dwell therein.

If a traveler far from home should arrive as a stranger,

Its warmth makes him forget both family and home.

Between hearing of its beauty and seeing it with one’s eyes,

A rivalry arises. Envy stirs between ear and eye.

When Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn founded Marrakesh in 1062, it wasn’t the charm of its landscape that drew him, but its strategic logic. Situated near the Tansīft River, shielded by the Atlas Mountains, and perfectly positioned for both desert and mountain campaigns, Marrakesh began as a fortified military encampment. But even an army needs water.

Early engineers — some say with Andalusian guidance — devised a remarkable solution: the khattārah system (الخطارات) of underground canals. These qanāts pulled fresh water from the mountains across long, dry stretches of land. They nourished people, irrigated gardens, and sustained the city itself. Without them, Marrakesh would have remained a mirage.

Geographers like al-Idrīsī and Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī described Marrakesh as “في وسط بلاد البربر”, i.e. in the heartland of the Berbers, where nomads once fought over grazing routes. One traveler observed that its ground was nothing more than “حجارة فوق حجارة”: stone upon stone.

Later writers recalled how the city bloomed:

وكانت بحائر عظيمة فبناها قصورًا وجامعًا وأسواقًا وفنادق، وجلب التجار إلى قيسارية عظيمة لم يبق فى مدن الأرض أعظم منها، وأمر بعمارتها أول سنة ٥٨٥ [١١٨٩]. ومدينة مراكش أكثر بلاد المغرب جنات وبساتين وأعناب وفواكه وجميع الثمرات، وكانت قبل ذلك يطير الطائر حولها فيسقط من العطش والرمضاء[4]…

He built upon its great reservoirs palaces, a grand masjid, markets, and caravanserais. He summoned traders to a vast central marketplace—larger than any in the cities of the world. He commissioned its construction at the beginning of 585 AH (1189 CE). Marrakesh became the most garden-filled city in the Maghrib, rich in vineyards, fruits, and all manner of produce. Before that, a bird flying over would fall from thirst and heat.

We walked through some of those old neighborhoods, dense with trees and shade even in the July heat. You could see how these groves made the city livable before the comforts of modern living were introduced.

One marvel remains to this day: the Ṣawmaʿa al-Kutubiyyīn (صومعة الكتبيين), or the Kutubiyya Minaret. Standing over 110 cubits tall, it dwarfed all others in the Muslim world of its time, and at its base was a remarkable timekeeping device known as the minjāna (المنجانة), a system of falling weights and ringing bells that audibly marked the hours throughout the city.

Ibn Baṭṭūṭah writes of his visit to Marrakesh:

ثم سافرت من سلا فوصلت إلى مدينة مراكش، وهي من أجمل المدن، فسيحة الأرجاء متسعة الأقطار كثيرة الخيرات، بها المساجد الضّخمة كمسجدها الأعظم المعروف بمسجد الكتبيين وبها الصومعة الهائلة العجيبة، صعدتها وظهر لي جميع البلد منها.[5]

"Then I traveled from Salé (سلا) and reached the city of Marrakesh. It is one of the most beautiful cities, expansive and full of bounties. It is home to enormous mosques, such as the great Masjid al-Kutubiyyīn, which has the tremendous and marvelous minaret (ṣawmaʿah). I ascended it, and from there the entire city lay before me."

Ibn Saʿīd describes the timekeeping system inside the minaret:

ومنارة جامعها المعروف بالكتبيّين طولها مئة وعشرة أذرع من الحجر وعلى باب جامعها ساعات ارتفاعها في الهواء خمسون ذراعا، ينزل عند انقضاء كلّ ساعة صنجة وزنها مئة درهم، يتحرك بنزولها أجراس يسمع وقعها من بعيد.[6]

“The minaret of the mosque, known as [Masjid] al-Kutubiyyīn, is 110 cubits tall and made of stone. At the gate of the mosque, there are clocks that sit 50 cubits above the ground. At the turn of every hour, a metal weight weighing 100 dirhams falls and rings the bells. The sound of the fall can be heard from afar.”

Even late at night, the old city of Marrakesh pulses with life. Horse-drawn carriages take the same narrow roads as cars and scooters, but the roads remain clean since the horses are equipped with pouches that catch their manure. The night markets bustle well past midnight, their stalls glowing under strings of lights. Crowds gather around impromptu performances and street games, many unfortunately involving chance or gambling. The square has a carnival-esque atmosphere, lively but largely disconnected from the deeper religious life of the city.

At the heart of this old city is Jemaa el-Fna. Established in the 11th century by the Almoravids, Jemaa el-Fnaa has served nearly a millennium as a center for trade, public gatherings, and performances. Over time it evolved into a gathering place for storytellers, musicians, herbalists, and food vendors. In 2001, UNESCO recognized it as a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”.

Marrakesh was not always a city of markets and minarets. Early Berber travelers whispered its name with alarm: “amur n akush”, they would say, “go quickly,” warning each other to pass through without delay. The Arabicized مراكش carries that old etymology, even though the city has become a gathering place for people from vastly different strains of life.

After settling in, we prayed maghrib at Masjid Argana, a relatively small local masjid. Everything there reflected Morocco’s deep Mālikī tradition. The adhān and iqāmah carried a distinct North African tone, and the imam recited in the style of warsh ʿan nāfiʿ which is the dominant qirāʾah in the Maghrib.

After entering, we grabbed leather bags from a pile to carry our shoes into the prayer hall. At the front, a bowl filled with smooth stones caught my eye. A muṣallī explained that it was for tayammum at times when water is unavailable. At the time of ṣalāh, every row of the masjid was packed. It was beautiful to witness how deeply the locals valued gathering to pray in jamāʿah.

The Mālikī madhhab first took root in al-Andalus, where students like Yahyā ibn Yahyā al-Laythī (d. 234 AH/848 CE), a direct student of Imām Mālik (d. 179 AH/795 CE), brought back his teachings from Madinah in the 8th century. Under his influence, Mālikism became the dominant school of law in the Umayyad courts of Cordoba. Around the same time, the school also began spreading across North Africa, especially through the scholarly circles of Qayrawan, led by towering figures like Saḥnūn ibn Saʿīd (d. 240 AH/854 CE), whose book al-Mudawwanah codified Mālikī fiqh. From there, Mālikism gradually expanded westward into Algeria and Morocco, and under the Almoravids in the 11th century it was made the official state madhhab. This consolidation under the Almoravids not only unified the legal landscape of North Africa but also bolstered Mālikism in Andalus, creating a shared religious and judicial culture that stretched from Cordoba to Marrakesh and into West Africa. Over time, the Mālikī school became inseparable from the region’s religious identity, shaping everything from court rulings to individual worship.

سبعة رجال: The Seven Saints

On Friday, we first visited Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf, to which I will dedicate a later travelogue biʾidhnillāh. We then embarked on the journey of visiting the سبعة رجال: seven righteous scholars and awliyāʾ whose resting places are preserved and cherished by the locals. The seven are:

1. Yūsuf ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣanhājī (d. 593 AH/1196 CE)

2. Al-Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ (d. 544 AH/1149 CE)

3. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Suhaylī (d. 518 AH/1185 CE)

4. Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Sabtī (d. 601 AH/1204 CE)

5. Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī (d. ~870 AH/1465 CE)

6. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Tabbāʿ (d. 914 AH/1499 CE)

7. ʿAbd-Allāh al-Ghazwānī (d. 936 AH/1529 CE)

Shaykh Mūsā Shāhīn Lāshīn writes in his commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, in the chapter on graves and their visitation:

كل ما سيأخذه الإنسان من سطح الأرض المتسع نصف متر في مترين، بل قد يشاركه في هذا الحيز آخرون على مر الزمان.

فهل من مدكر؟ إن لم نتعظ بالقول فها هي قبور الآباء والأجداد، شرع الله زيارتها، والاتعاظ بمن فيها، لقد وجدوا ما وعدهم ربهم حقاً، ولم يبق معهم سوى عملهم، ونحن على الطريق سائرون، وإلى ما انتهوا إليه منتهون، فقط نحن مؤجلون، لكننا لا محالة لاحقون.[7]

All that a human being will take from this earth is half a meter by two meters (i.e. a grave-sized patch of soil). And even that small space may, over time, be shared with others.

{Fa hal min muddakir} – so will anyone take heed?! If words do not move us, then here lie the graves of our forefathers. Allah has legislated the visitation of graves [so that] we may reflect and take lessons from those who lay in them. They have found the promise of their Lord to be true, and nothing remains with them but their deeds. We are walking the same path and heading towards the same terminus. They have only preceded us; we are simply deferred. But we will, without question, join them.

Alhamdulillah, Allah blessed us with the opportunity to visit all of their graves on this trip. When I first attempted to visit Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ’s grave, it was closed off. We were barely able to make it inside the outer structure, only to find that the area where his actual grave sits was sealed off again. I was very saddened that we weren’t able to stand there at the grave and read some selections of his book, Al-Shifā, as I had looked forward to doing for a long time. Historically, scholars have often completed maqraʾahs (hadith auditions) by the graves of the compilers or other scholars.[8] When scholars narrated hadiths to their students whilst sitting by the blessed grave of Rasūl-Allāh ﷺ, they would say “قال صاحب هذا القبر… (The one who lies in this grave said…).”[9]

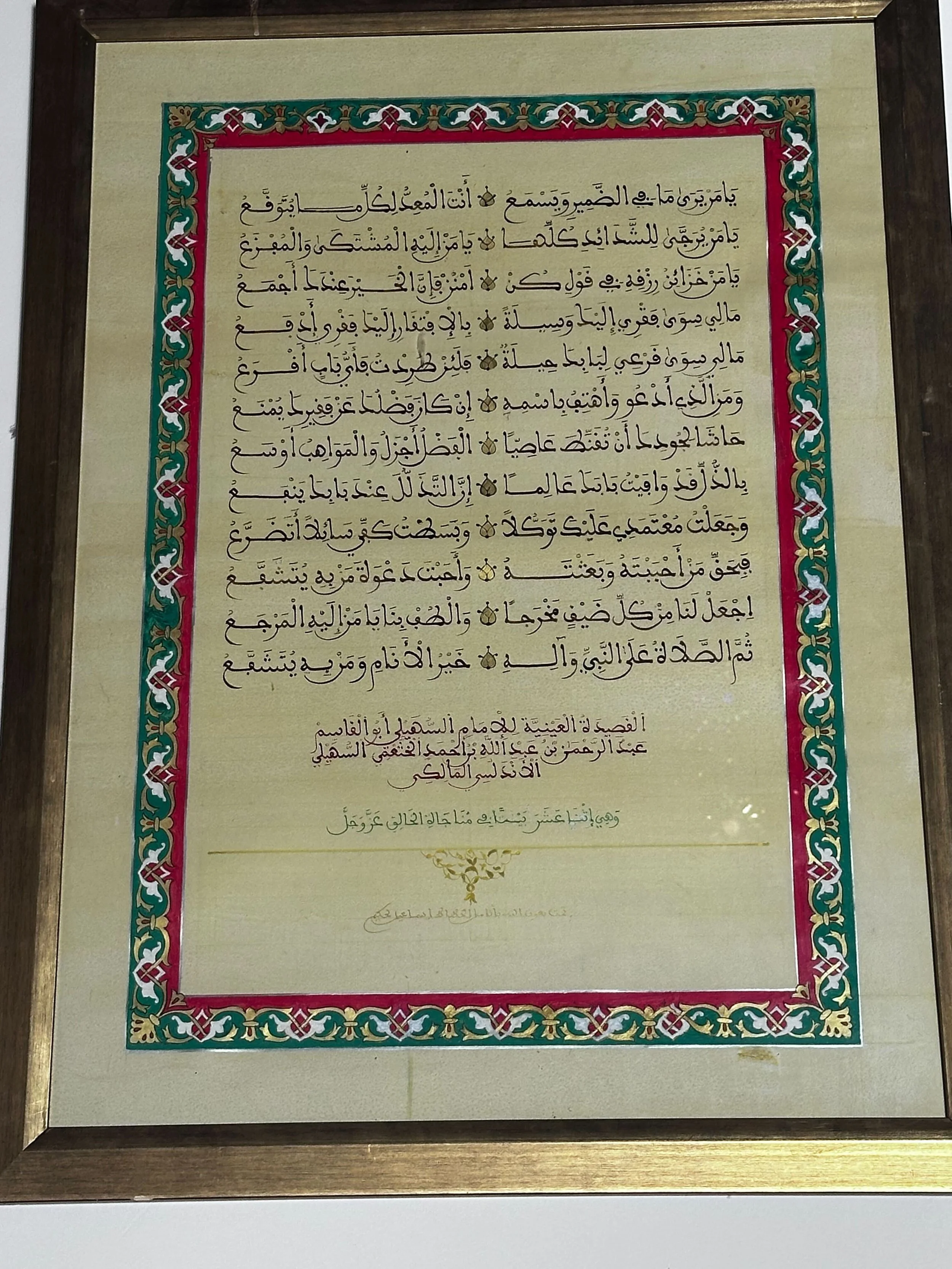

We then prayed jumuʿah at the Kutubiyyah, and proceeded to visit Imam al-Suhaylī. He authored the classic Al-Rawḍ al-Unf, a widely cited commentary on the Sīrah of Ibn Hishām. The book is printed in eight volumes, a feat made even more incredible by the fact that al-Suhaylī was reportedly blind.[10] On the wall near his grave was one of his poems known as Al-ʿAyniyyah (العينية), written in the classic maghribi script. Ibn Khallikān relates that al-Suhaylī said, “Never does one ask Allah the Exalted for a need by means of [this poem] except that He grants it.”[11] My heart was still heavy since we were unable to visit Qādī ʿIyāḍ; I read the poem and asked Allah to allow us to visit his grave.

Of the graves of the seven awliyāʾ, only Imām al-Suhaylī’s was inside a large cemetery; the rest stood as individual mausoleums across the old city of Marrakesh. I noticed that, unlike most cemeteries I’ve visited, the graves were not all facing the same direction. According to most scholars, burying the deceased on their right side facing the qiblah is obligatory – except for the Mālikīs, who consider it recommended but not required.[12] We were also able to visit the grave of Imām al-Jazūlī. He is the famous author of Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt, a renowned collection of ṣalawāt upon the Prophet ﷺ. The entire book is recited on Thursdays at his zāwiyah. We conveyed our salām from outside, but did not have sufficient time to go inside.

We then tried once more to visit Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ, and by the faḍl of Allah, we were able to enter. This opening came after a long day spent trekking across Marrakesh on foot in order to visit the seven tombs. We were thirsty and tired, without cash, and our phone batteries had been depleted, leaving me unable to retrieve my digital copy of Al-Shifā. As I sat next to the grave, a man who I did not know and never saw again walked up to me and handed me a book; he said something to the effect of: “You look like you would benefit from this.” I looked at the book he had placed in my hands, and found nothing other than Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ’s Al-Shifā. I opened to a random page and found the chapter on the blessed perspiration of the Prophet ﷺ – a reassuring sign after a long day spent walking under the sun of Marrakesh. Against all apparent material means, we were able to read selections from the text right next to the author’s grave. May Allah accept the works of these scholars as a ṣadaqah jāriyah and allow many more generations to benefit from them.

⸻

In 585/1189, Al-Manṣūr Abū Yūsuf, the third Almohad ruler, initiated major urban developments in Marrakesh, channeling water from his palace into the heart of the city:

أن أرسل فى وسط المدينة ساقية ظاهرة ماؤها ماء قصره المكرم، تشق المدينة من القبلة إلى الجوف، وعليها السقايات لسقي الخيل والدواب واستقاء الناس، فهي اليوم أشرف مدن الدنيا وأعدلها هواء[13]

He directed an open canal through the center of the city, its water drawn from his palace, flowing from the south to the north. Along its course stood fountains for watering animals and for people to draw water. Today it is among the noblest and healthiest of cities.

But perhaps most remarkable was the maristān, or hospital, established during this period. As mentioned in the book Al-Istibṣār, it was no mere infirmary but a place of healing and dignity:

ووضع دار الفرج فى شرقى الجامع المكرم، وهو مارستان المرضى، يدخله العليل فيعاين ما أعد فيه من المنازه والمياه والرياحين والأطعمة الشهية والأشربة المفوهة، ويستطعمها ويسيغها فتنعشه من حينه بقدرة الله تعالى.[14]

He established Dār al-Faraj to the east of the great masjid, which is a maristān for the sick. As patients entered they would see gardens, water, fragrant plants, delicious food, and sweet drinks. They would enjoy the food and drink and thereby be nourished, by the power of Allah.

In the same year, he summoned scholars to teach the ḥadīth of the Prophet ﷺ, renewing the city’s commitment to sacred knowledge:

وكان ذلك سنة خمس وثمانين وخمسمائة، ثم استدعى العلماء ورواة الحديث وأهل الفنون المختلفة، فجلبوا إليه من الأقطار، فكثر فيها العلماء وامتلأت بوجوه أهل البلاد من كل صقع

He then summoned scholars, hadith narrators, and the experts of every craft and science, and they came to him from all distant lands. The city came to host an abundance of scholars and notables from every region.

The Almohads (al-muwaḥḥidūn), known for their religious zeal and rather severe theological approach, instituted reforms with a degree of force:

وأهل مراكش يأكلون الجراد، ويباع فيها كل يوم منه أحمال، وعليه قبالة، وكان أكثر الصنائع بمراكش متقبلة عليها مال لازم مثل سوق الدخان والصابون وغيرهما، وكانت القبالة على كل شيء يباع، فلما صار الأمر للموحدين قطعوا تلك القبالات وأراحوا منها، واستحلوا قتل المتقبلين لها، فلا ذكر لها في بلادهم.

The people of Marrakesh eat locusts, and every day loads of them are sold there with a fixed tax. Most of the trades in Marrakesh were subject to a necessary tax, such as the tobacco and soap markets, among others. There was a tax on everything that was sold. When the Almohads took over, they abolished these taxes and relieved the people of them. They considered it permissible to kill those who collected the taxes, and so there is no mention of them in their lands.[15]

Marrakesh also saw decline. After the golden age of the Almohads, poets and travelers wrote of its decadence. One satirist said:

يطوف التجار بمراكش طواف الحجيج ببيت الحرام

تروم النزول فلا تستطيع، لشرب الخمور وهتك الحرم[16]

Merchants circle Marrakesh like pilgrims around the Sacred House;

You seek lodging but find none, for the wine flows and sanctity is violated.

Even Ibn Baṭṭūṭah said:

ما شبهته إلا ببغداد، إلا أن أسواق بغداد أحسن.[17]

I found that it resembled Baghdad, except Baghdad’s markets are better.

This is the story of great cities. As Allah تعالى says:

﴾وَكَمْ أَهْلَكْنَا مِن قَرْيَةٍ بَطِرَتْ مَعِيشَتَهَا﴿

And how many a city We destroyed that exulted in its livelihood… (Qur’an 28:58)

Throughout our travels in Morocco, I was struck by the widespread poverty and apparent lack of investment in social welfare by the government. Men, women, and children could all be seen working to make a living, performing whatever menial jobs they could to get by. Nonetheless, the country and its people exuded beauty and they were clearly proud of their culture and history.

We spent the next couple of days exploring other sites in Marrakesh, which I will continue to detail in a future travelogue with the permission of Allah.

والحمد لله رب العالمين

Notes

[1] Aḥmad al-Nāṣirī, Al-Istiqṣā li-Akhbār Duwal al-Maghrib al-Aqṣā (Casablanca: Dār al-Kitāb 1997), 1:85.

[2] Vernon O. Egger, A History of the Muslim World to 1750 (New York: Routledge 2018), 44.

[3] Al-Idrīsī, Nuzhah al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq (Beirut: ʿĀlam al-Kutub), 1:222.

[4] Al-Istibṣār fī ʿAjāʾib al-Amṣār (Baghdad: Dār al-Shuʾūn al-Thaqāfiyyah 1986), 1:210.

[5] Ibn Baṭṭūṭah, Riḥlah Ibn Baṭṭūṭah (Ribat: Akādimiyyah al-Mamlakah al-Maghribiyyah), 4:229.

[6] Aḥmad Ibn Faḍl-Allāh al-ʿUmarī, Masālik al-Abṣār fī Mamālik al-Amṣār (Abu Dhabi: Al-Majmaʿ al-Thaqāfī), 4:197.

[7] Mūsā Shāhīn Lāshīn, Fatḥ al-Munʿim Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (Dār al-Shurūq, 2006), 4:254.

[8] Garrett A. Davidson, Carrying on the Tradition: A Social and Intellectual History of Hadith Transmission across a Thousand Years (Boston: Brill 2020), 90.

[9] Abū Bakr b. al-ʿArabī, Qānūn al-Taʾwīl (Jeddah: Dār al-Qiblah lil-Thaqāfah al-Islāmiyyah) Editor’s Introduction, 84; “وكان رحمة الله عليه يقضي جلّ أوقاته في الروضة الشريفة بين القبر والمنبر يستمع إلى أحاديث العلماء الأعلام وهم يقولون: قال صاحب هذا القبر .. وحدث ابن العربي تلاميذه بكل ما سمع في الروضة الشريفة وهو فخور بذلك.”

[10] Rawḍ al-Unf (Beirut: Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabī), Editor’s Introduction, 1:8.

[11] Ibn Khallikān, Wafayāṭ al-Aʿyān (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir), 3:143; “وقال ابن دحية: أنشدني وقال: إنه ما سأل الله تعالى بها حاجةً إلا أعطاه إياها”.

[12] Abd al-Raḥmān al-Jazīrī, Al-Fiqh ʿalā al-Madhāhib al-Arbaʿah (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah), 1:485: “ويجب وضع الميت في قبره مستقبل القبلة، وهذا الوجوب متفق عليه إلا عند المالكية، فإنهم قالوا: إن هذا مندوب لا واجب.”

[13] Al-Istibṣār, 1:210.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Al-Ḥimyarī, Al-Rawḍ al-Muʿṭar fī Khabar al-Aqṭār (Beirut: Muʾassasah Nāṣir lil-Thaqāfah), 541.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibn Baṭṭūṭah, Riḥlah Ibn Baṭṭūṭah (Ribat: Akādimiyyah al-Mamlakah al-Maghribiyyah), 4:230.

Mufti Hussain Kamani is the Director of the Qalam Seminary and a senior faculty member, where he teaches hadith, fiqh, and tazkiyah. With over two decades of experience in teaching and community leadership, he has mentored and trained over a thousand students, many of whom now serve as imams, chaplains, educators, and leaders across the United States.