Between Confidence and Competence: Arabic Through the Dunning-Kruger Lens

Ustadh Obaidullah Ahmad

Over the past fifteen years of teaching Arabic, I have noticed some key psychographics among students that ultimately impact their long-term learning of the language. One is the contrast between students just beginning and those further along the path. Beginners often soar with confidence. They have learned to identify a few patterns, perhaps match endings to grammatical cases, and suddenly feel as though they have unlocked the code to Arabic. However, students who’ve spent months building real skills begin to notice just how vast, layered, and demanding the language really is. Their confidence dips, not because they have become worse, but because they have finally gained enough perspective to see what mastery actually looks like.

I recently learned that this dynamic isn’t unique to Arabic — it is a textbook example of what psychologists call the Dunning-Kruger effect. I am grateful to my student, Shaima, for introducing me to this study.

In their 1999 study, David Dunning and Justin Kruger identified a pattern in how people perceive their own competence.1 Those with lower skill levels tend to overestimate their abilities, while those with greater skill often underestimate themselves. The researchers mapped this trajectory as a kind of learning curve with memorable labels for each phase. These stages have become a useful lens in education, and they show up regularly in my classroom.

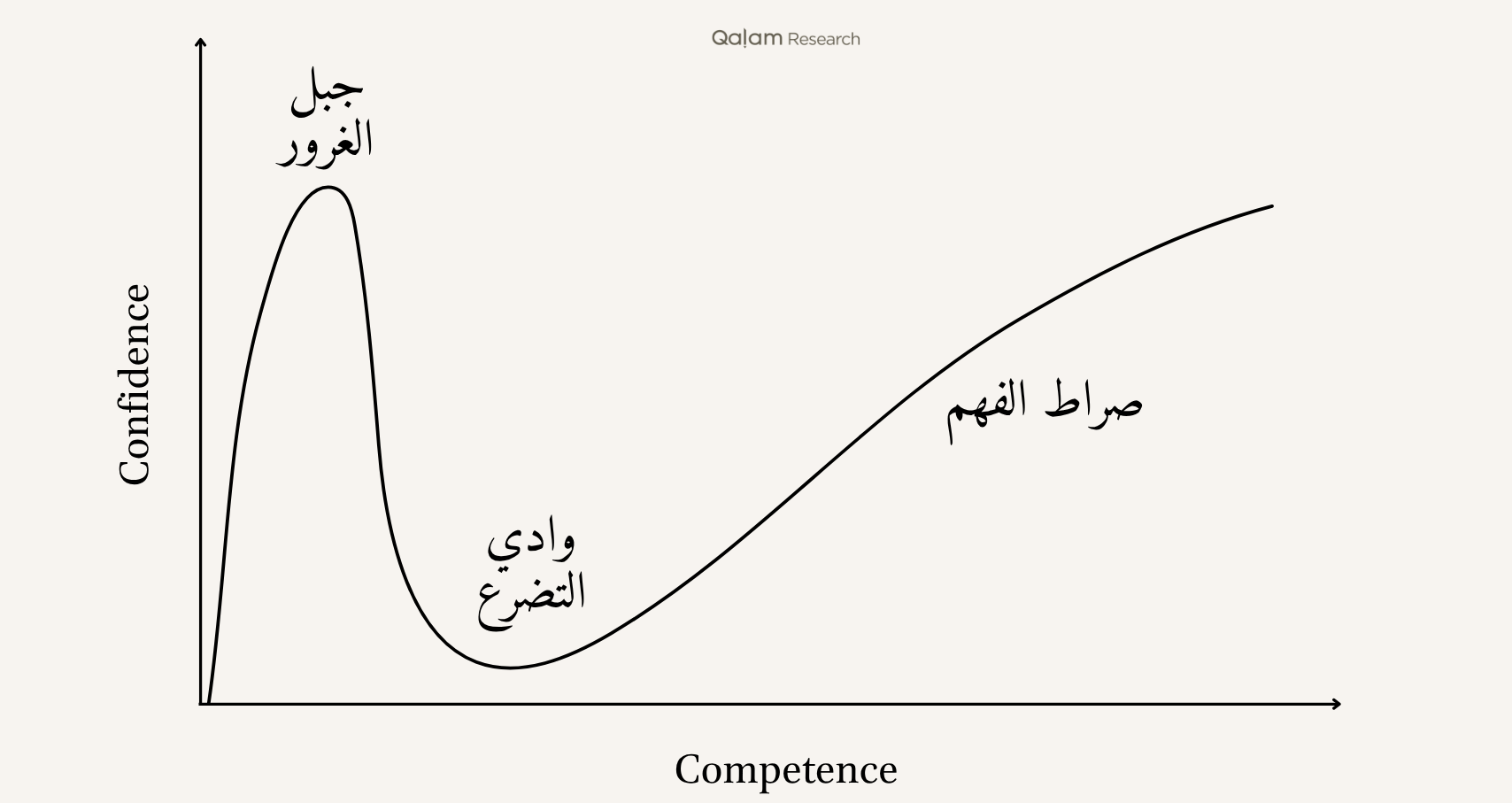

In the early stages of the seminary’s one-year Arabic program, students are introduced to foundational grammar concepts, one of the first being the states of nouns: rafʿ, naṣb, and jarr. Once they learn to recognize these states by vowel endings, many feel like they have cracked the code. I have seen students beam with confidence simply because they can spot a ḍammah or a kasrah. This is what Dunning and Kruger referred to as the “Peak of Mount Stupid”, or what we can refer to as Jabal al-Ghurūr: the Mountain of Delusion. This is that early high, where a little knowledge feels like a lot. But grammar in Arabic isn’t just about labeling endings; it is about understanding structure. Real comprehension occurs when a student can explain why a word is in that state, what governs it, and how it relates to the words around it. This distinction — between identifying something and truly understanding it — often takes time to settle in.

One of the clearest reality checks comes when students step outside the curated safety of the workbook. Though we study grammar and ṣarf through examples drawn from the Quran, the exercises are structured, targeted, and predictable, designed to isolate and reinforce specific concepts. When students then open a muṣḥaf and try to apply what they have learned, it can feel like they have wandered into “the wild”. Familiar patterns show up in unfamiliar ways. Confidence dips. This is what the Dunning-Kruger framework calls the “Valley of Despair” or in our context, Wādī al-Taḍarruʿ: the Valley of Humble Realization. This is where the student begins to recognize their limitations, their gaps in understanding, and the importance of consistent effort. I remind them that struggle is not failure; it is growth. In fact, it is the kind of productive discomfort we encourage at the seminary, where we emphasize adopting a growth mindset. It is a reminder that real learning feels difficult because it is supposed to.

As the year progresses, students begin vowelizing un-voweled Arabic texts. By this point, students may feel confident, especially if they have had success parsing Quranic verses. But vowelization is a different skill. It requires transferring grammar and ṣarf knowledge into a new mental process, one that is not just analytical but predictive. Some students assume their parsing skills will carry over naturally, and they tune out during the early vowelization lessons. The irony is that these early sessions are crucial, not because they’re difficult, but because they lay the groundwork for building a repeatable method. The students who dismiss that stage often find themselves scrambling later, wondering why the skill isn’t clicking.

As vowelization becomes a regular part of classwork, two kinds of students tend to emerge. The first group vowels accurately and can explain their reasoning. They have internalized the grammar and developed a process, but they may still struggle to produce a clear translation. I remind them that translation is its own skill. It demands familiarity with idiomatic usage, tone, and context, and that only comes with more exposure and reading. The second group vowels well, but can’t articulate why. They’re often relying on prior exposure to Arabic or instinct, and while that can carry them through beginner texts, it eventually plateaus. Without a process, they get stuck when the patterns grow more complex. Both groups are progressing, but only one is climbing what Dunning and Kruger called the “Slope of Enlightenment”, or for our purposes, Ṣirāṭ al-Fahm: The Path of Deep Understanding. It is a gradual, often humbling climb, but one that leads to stability and clarity over time.

This, to me, is where the Dunning-Kruger effect becomes more than just a clever psychological graph — it becomes a teaching lens. It helps me stay patient when a student is overconfident and compassionate when a skilled student is discouraged. It reminds me to guide students not just in what to learn, but in how to understand their learning process. In a subject as vast and humbling as Arabic, self-awareness is as critical as grammar charts. The goal isn’t just confidence, but calibrated confidence is: the kind that is grounded in process, sharpened by struggle, and matured by time.

As you proceed through your Arabic studies, keep in mind how much your perspective shapes your progress. The Dunning-Kruger effect reminds us that confidence and competence don’t always align, especially in the early or in-between stages. That is why it is so important to be honest with yourself about where you stand. Don’t just say, “I’m struggling.” Ask: what exactly is tripping me up? Be specific. Be nuanced. The more precise you are, the more likely you are to break through.

No matter where you fall on the curve, whether you’re feeling overconfident or overwhelmed, know that growth is possible. Arabic rewards effort. Make plenty of duʿāʾ, and don’t obsess over the outcome. Learn to enjoy the journey: the highs, the lows, and all the little wins in between.

[1] David Dunning & Justin Kruger, “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77. 1121-34. 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121.

Ustadh Obaidullah Ahmad is a faculty member and Head of the Arabic department at Qalam Seminary.