Morocco: Pages of a Living Tradition | Pt. II

Mufti Hussain Kamani

Part II: Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf

This is Part II of a travelogue series. Read Part I here.

Early on a Friday morning, we made our way through the narrow streets of Marrakesh toward Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf. Along the way, we passed a variety of small shops selling clothing, tagines, and leather goods. After paying 50 dirhams each for entry, we stepped into one of the most historically significant institutions of learning in the Islamic world, located next to the grand masjid that shares its name. Visiting it on this trip stirred an emotion that was part awe, part sorrow.

Rashīd al-Afāqī and Samīr Ait Umghār’s detailed study, Tārīkh Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf bi-Marrākush, offers valuable insights into the institution’s history, its construction, and the role it played in religious preservation. This madrasah ranks among Morocco’s most prestigious institutions of Islamic learning. Over generations, it nurtured scholars, jurists, Qur’an reciters, and students from far-off regions such as Sūs and the High Atlas, serving as both a residence and an intellectual sanctuary.

The exact origins of the madrasa remain a topic of scholarly debate. The most widely accepted view, supported by Ibn Baṭṭūṭah, credits its formal founding to Sultan Abū al-Ḥasan al-Marīnī in the 14th century.

Ibn Baṭṭūṭah praised the madrasah in his Riḥlah:

وبمراكش المدرسة العجيبة التي تميزت بحسن الوضع وإتقان الصنعة، وهي من بناء الإمام مولانا أمير المسلمين أبي الحسن، رضوان الله عليه.[1]

And in Marrakesh is the wondrous madrasa, distinguished by the excellence of its design and the perfection of its craftsmanship. It was built by the noble Imām, our master, the Commander of the Muslims, Abū al-Ḥasan — may God be pleased with him.

Madrasa Ibn Yūsuf is often confused with the nearby Masjid Ibn Yūsuf. The masjid, founded earlier in 514 AH / 1120 CE by the Almoravid prince ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn, was also known as Jāmiʿ al-Saqāyah and Jāmiʿ al-Murtaḍā. It was later rebuilt in 654 AH / 1256 CE by the Almohad caliph al-Murtaḍā. While the masjid served as a teaching space for students of the neighboring madrasa, the madrasa itself primarily functioned as student housing, especially during periods of scholarly fluctuation. This mirrors the relationship between Marinid madrasas in Fez and the University of al-Qarawiyyīn.

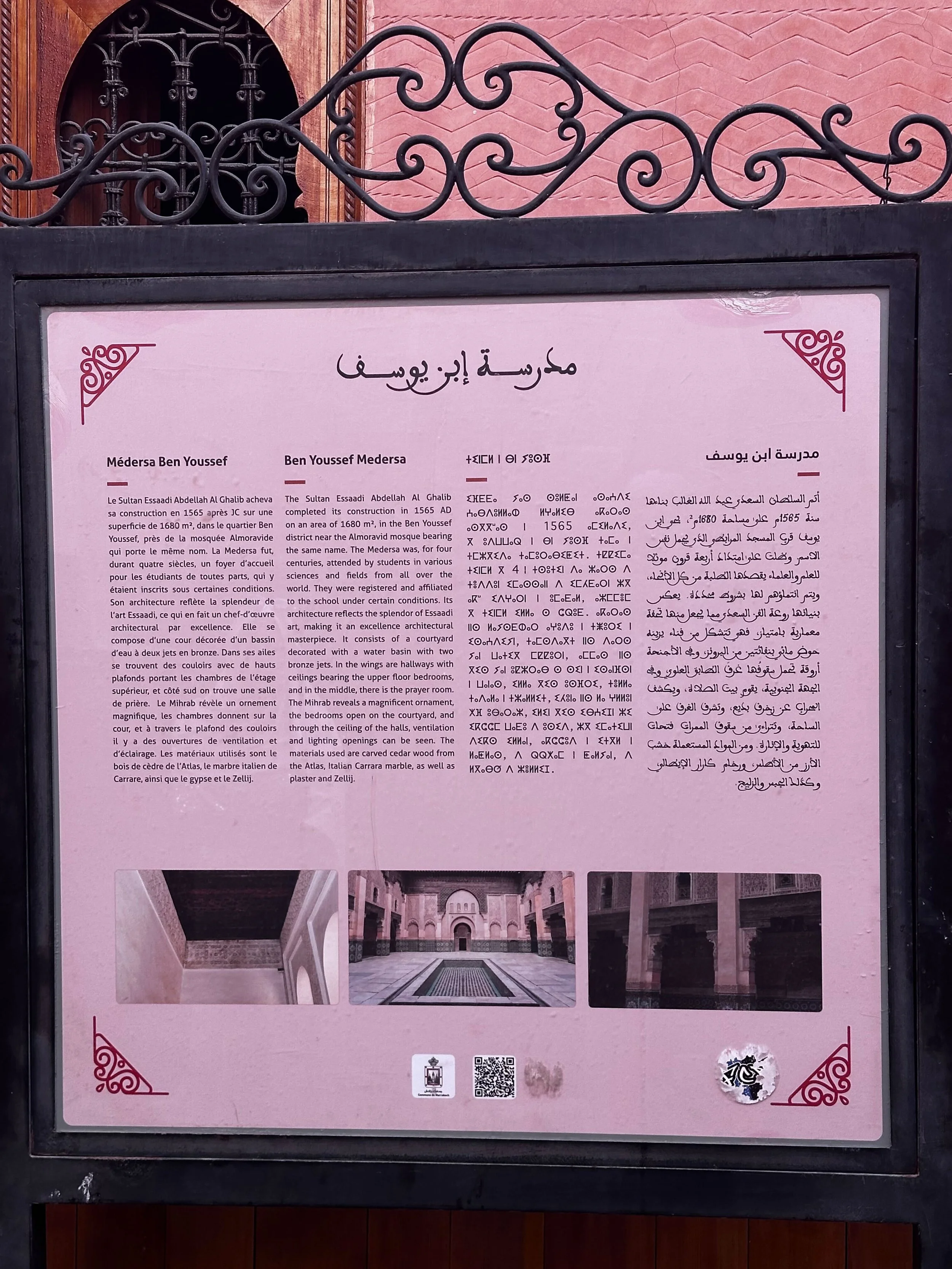

The madrasa is a two-story structure covering approximately 1,700 square meters. It centers on a spacious courtyard with a marble fountain and includes student dormitories, a prayer hall, and what was once a library of rare manuscripts. The architecture itself has been an object of study for scholars, comprising zellij mosaics, cedar wood carvings, stucco calligraphy, and marble.

Now, Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf serves as little more than an artifact or art installation. But it used to be more than just a beautiful building. It once bustled with intellectual life. Every Friday, its courtyard hosted a manuscript market known as Dalālat al-Kutub (دلالة الكتب). Collectors, scholars, and students would gather to buy and sell rare texts. The courtyard also served as a copying station where scribes carefully transcribed manuscripts, ensuring that the Islamic intellectual tradition was preserved and studied.

At its height, the madrasa was a center of Islamic learning where students memorized the Qur’an and studied Mālikī fiqh, Arabic grammar, and logic.

On the ground floor, each classroom was connected to a smaller side room, likely areas where students would prepare their lessons before entering the main classroom. I sat in one of those rooms and recited a few verses of the Quran. The acoustics carried the sound with a solemn beauty. These walls once echoed with the voices of hundreds or thousands of students practicing ṣarf patterns, reading classical texts, reciting Quran, and engaging in dhikr.

As the sunlight streamed into the room, I imagined the scene centuries ago: students in turbans, books in hand, filling the courtyard with discussion and debate. Each ṣalāh time would pause the learning. Their teachers guided them not just in academic pursuits but in adab and tazkiyah.

إِنَّمَا يَعْمُرُ مَسَاجِدَ ٱللَّهِ مَنْ آمَنَ بِٱللَّهِ وَٱلْيَوْمِ ٱلْآخِرِ وَأَقَامَ ٱلصَّلَوٰةَ وَءَاتَى ٱلزَّكَوٰةَ وَلَمْ يَخْشَ إِلَّا ٱللَّهَ فَعَسَىٰٓ أُو۟لَـٰٓئِكَ أَن يَكُونُوا۟ مِنَ ٱلْمُهْتَدِينَ

"Only those shall maintain the mosques of Allah who believe in Allah and the Last Day, perform the prayer, give zakāh, and fear none but Allah. It is they who are expected to be on true guidance." (Sūrat al-Tawbah, 9:18)

In those moments, my heart began to feel heavy. This place had once been a cradle of guidance. Today it is a historical monument and museum, listed on TripAdvisor as one of Marrakesh’s top tourist spots. Around me were tourists in summer clothing, queuing to take social media photos in halls once sanctified by students of knowledge.

The scene brought to mind a powerful hadith of the Prophet ﷺ narrated by ʿAlī (may Allah be pleased with him):

"A time will come upon the people when nothing will remain of Islam except its name, and nothing will remain of the Qur’an except its script. Their mosques will be full but devoid of guidance. Their scholars will be the worst of those under the heavens. From them will emerge tribulations, and to them will they return." (al-Bayhaqī, Shuʿab al-Īmān)

Alḥamdulillāh, Marrakesh is still home to righteous mashāyikh. Though the venue may have changed, the gatherings of sacred knowledge still take place and students still travel to attend them. As the verse reminds us:

فَأَمَّا ٱلزَّبَدُ فَيَذْهَبُ جُفَآءًۭ ۖ وَأَمَّا مَا يَنفَعُ ٱلنَّاسَ فَيَمْكُثُ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ

"As for the scum, it vanishes like foam cast off; but what benefits people remains on the earth." (Sūrah al-Raʿd, 13:17)

People of knowledge are not bound by structure or title. The madrasah’s true purpose is served not by its architecture, but by the scholars and students who continue to implement the knowledge that was once transmitted within its walls. As the saying goes:

السيف بالساعد، لا الساعد بالسيف

It is the arm that gives strength to the sword, not the sword to the arm.

For the remainder of my visit at the madrasah, a single question remained in my heart: How did we arrive at this point?

Last year as part of the Qalam Hadith Tour, I traveled with my dear colleagues Qari Noman Hussain and Mufti Muntasir Zaman to Uzbekistan. We witnessed a similar state of decline in the madāris of Bukhara and Samarkand. These were once centers of knowledge and home to scholars whose works we still study; now, these cities are full of buildings that people visit for their architecture and not for the knowledge transmitted within. I have not yet visited Andalusia or Iraq, but from what I have read, their once grand Islamic institutions met the same fate. Today, they exist primarily as cultural landmarks, and their students have been replaced by tourists.

The answer at least partially lies in our failure to preserve what we once built. Successive dynasties often tried to erase the legacy of their predecessors, even if that meant dismantling the very institutions they had inherited.

The Andalusi historian al-Ḥasan ibn al-Wazzān (Leo Africanus) described the masjid and madrasah of Ibn Yūsuf in his book Waṣf Ifrīqiyah (Description of Africa) as follows:

In the middle of the city is a mosque of exceptional beauty built by ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf, one of the early kings of Marrakesh. It is known as the Masjid of Ibn Yūsuf. But ʿAbd al-Muʾmin, a king who came after the Lamtūnid dynasty, demolished it and rebuilt it for one reason: to erase the name of ʿAlī and replace it with his own. His effort went in vain because to this day, the people continue to call it by its original name: the Masjid of Ibn Yūsuf.[2]

Even Imām Mālik advised the Abbasid caliph not to reconstruct the Kaʿbah after ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān had partially demolished and rebuilt it, fearing that every new ruler would seek to stamp his own legacy on the sacred mosque:

وَقَدْ هَمَّ الْمَهْدِيُّ بْنُ الْمَنْصُورِ الْعَبَّاسِيُّ أَنْ يُعِيدَهَا عَلَى مَا بَنَاهَا ابْنُ الزُّبَيْرِ، وَاسْتَشَارَ الْإِمَامَ مَالِكَ بْنَ أَنَسٍ فِي ذَلِكَ، فَقَالَ: إِنِّي أَكْرَهُ أَنْ يَتَّخِذَهَا الْمُلُوكُ مَلْعَبَةً. [..] فَهَذَا يَرَى رَأْيَ ابْنِ الزُّبَيْرِ، وَهَذَا يَرَى رَأْيَ عَبْدِ الْمَلِكِ بْنِ مَرْوَانَ.[3]

The Abbasid al-Mahdī b. al-Manṣūr considered restoring the Kaʿbah to the structure built by Ibn al-Zubayr, so he consulted Imām Mālik. The imam responded: “I fear that rulers will begin to treat it like a toy: this one following the opinion of Ibn al-Zubayr, that one following ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān.

This points to a deeper illness: when our sacred institutions become tethered to political power, they rise and fall with it. A part of the solution may be to separate madrasahs from the state, securing their future with independent awqāf run by trusted bodies and scholars, not political entities. The sacred mission of education should not be contingent on the ruling regime of the day.

It is no coincidence that many senior companions of the Prophet ﷺ avoided political office and stayed away from major power struggles. They knew that the dīn must remain above politics. While we have the time and the freedom, we must do the same — strategically securing our seminaries, tradition, and ability to practice and transmit Islam.

It is possible that the decline of these institutions is not merely due to political transformations. It may also reflect a spiritual decline within us. Sometimes our lack of sincerity, complacency with Allah’s favors, or arrogance that follows success bring about our own collapse.

Yaḥyā ibn Muʿādh al-Rāzī, an early figure in taṣawwuf, once rebuked the scholars of his time with piercing words:

يا أصحاب العلم! قصوركم قيصرية وبيوتكم كسروية وأثوابكم ظاهرية وأخفافكم جالوتية ومراكبكم قارونية وأوانيكم فرعونية ومآثمكم جاهلية ومذاهبكم شيطانية فأين الشريعة المحمدية؟[4]

O people of knowledge! Your palaces resemble those of Caesar, your homes those of Kisrā, your garments those of Ṭāhir, your shoes those of Jālūt, your mounts those of Qārūn, your vessels those of Pharaoh, your sins those of jāhiliyyah, and your methodologies those of Shayṭān. So where is the sharīʿah of Muḥammad (ﷺ) [in your practice]?

What was once a class of scholars known for zuhd, humility, and dignity became one of self-indulgence and showmanship.

The great scholar Ibn al-Ḥājj al-Fāsī lamented this tragic reversal:

كَانَ النَّاسُ يَقْتَبِسُونَ أَثَارَ الْعَالِمِ وَيَهْتَدُونَ بِهَدْيِهِ وَيَرْجِعُونَ عَنْ عَوَائِدِهِمْ لِعَوَائِدِهِ فَانْعَكَسَ الْأَمْرُ فَصَارَ مَنْ لَا عِلْمَ عِنْدَهُ مِنْ الْأَعَاجِمِ وَغَيْرِهِمْ يُحْدِثُونَ أَشْيَاءَ [..] فَيُسْكَتُ لَهُمْ عَنْ ذَلِكَ، ثُمَّ يَأْتِي الْعَالِمُ فَيَتَشَبَّهُ بِهِمْ فِي فِعْلِهِمْ … فَجَاءَ مَا قَالَ صَاحِبُ الْأَنْوَارِ - رَحِمَهُ اللَّهُ - سَوَاءً بِسَوَاءٍ: وَيْلَكُمْ يَا مَعَاشِرَ الْعُلَمَاءِ السُّوءِ الْجَهَلَةِ بِرَبِّهِمْ جَلَسْتُمْ عَلَى بَابِ الْجَنَّةِ تَدْعُونَ النَّاسَ إلَى النَّارِ بِأَعْمَالِكُمْ فَلَا أَنْتُمْ دَخَلْتُمْ الْجَنَّةَ بِفَضْلِ أَعْمَالِكُمْ وَلَا أَنْتُمْ أَدْخَلْتُمْ النَّاسَ بِهَا بِصَالِحِ أَعْمَالِكُمْ قَطَعْتُمْ الطَّرِيقَ عَلَى الْمُرِيدِ وَصَدَدْتُمْ الْجَاهِلَ عَنْ الْحَقِّ فَمَا ظَنُّكُمْ غَدًا عِنْدَ رَبِّكُمْ إذَا ذَهَبَ الْبَاطِلُ بِأَهْلِهِ وَقَرَّبَ الْحَقُّ أَتْبَاعَهُ.[5]

“People used to follow in the footsteps of the scholars and take guidance from them. They would abandon their own customs in favor of [those of the scholars]. Now matters have been reversed. Those without knowledge invent blameworthy practices [..], no one speaks against them, and then the scholar comes along and imitates them…

And so the words of the author of al-Anwār, may Allah have mercy on him, have come to pass precisely as he said: ‘Woe to you, corrupt scholars, ignorant of your Lord! You sit at the gates of Paradise, calling people to the Fire through your actions. You have not entered Paradise through the virtue of your own deeds, nor have you led others into it through your righteous conduct. You have blocked the path of the seeker and turned the ignorant away from the truth. So what do you think your Lord will do tomorrow, when falsehood perishes with its people and truth draws near with its followers?’”

Where once the public modeled themselves on the ʿulamāʾ, today some ʿulamāʾ chase the fashions and interests of the public. The standard-setters have become imitators.

Madrasahs like that of Ibn Yūsuf required generations of effort: visionary founders, generous patrons, sincere teachers, hardworking students, and entire ecosystems of scholarship to allow them to thrive. When that chain is broken by war, neglect, or a loss of purpose, these institutions hollow out. Their physical walls remain, but their soul is gone.

Today, tourists pass through the halls of Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf wearing vacation attire. Their clothing and demeanor stand in stark contrast to the very adab that these halls were built to cultivate. This has ramifications beyond the walls of the madrasah itself, as Syed Naquib al-Attas writes about in The Concept of Education in Islam:

Taʾdīb is then the precise and correct term to denote education in the Islamic sense. [..] Loss of adab means the loss of the capacity for discernment of the right and proper places of things, resulting in the levelling of all to the same level; in the confusion of the order of nature as arranged according to their marātib and darajāt; in the undermining of legitimate authority; and in the inability to recognize and acknowledge right leadership in all spheres of life. The solution to this problem is to be found in education as a process of taʾdīb.[6]

In the West today, many of us are benefiting from newly built seminaries and institutes. They are filled with hope, sincerity, and momentum. But we must ask ourselves: What are we doing to ensure that they last beyond us? Have we built them on a foundation of independent sustainability, spiritual humility, and scholarly excellence?

In the second volume of The Venture of Islam, Marshall Hodgson writes about a key period wherein madrasahs proliferated, particularly at the time of Niẓām al-Mulk, despite the political fragmentation of the ummah. He argues that the systematization of madrasah curricula and creation of ʿulamāʾ networks aided these institutions in attaining autonomy from the state and military:

“The madrasahs did not, as it turned out, furnish leadership for a great centralized bureaucracy; yet they did serve the cause of Muslim unity in a different way. As the madrasahs spread throughout lslamdom, their relatively standardized common training allowed them to foster an esprit de corps among Jamāʿī-Sunnī 'ulamā' independent of local political circumstances. Thus the madrasah became an important medium for perpetuating, in a still more strongly institutionalized form, that homogeneity in the Muslim community which had begun with the pristine community in Medina. In the time of the Marwanids this had been maintained as a spirit of solidarity among the limited numbers of the ruling class, and in classical 'Abbasi times it had been carried on by the 'ulama' in the mosques, with their chains of hadith transmitters from teacher to pupil across the generations. Now, with the loss of the political framework of the caliphal state and of the central role of Baghdad, something further was needed to meet the old threat of disintegration. The relatively formal pattern of the madrasah carried on the task of maintaining essential unity in the community's heritage from Muḥammad [ﷺ], and in the immediate confrontation with God in all aspects of life, which he stood for. The new endowed institutions had a large stake in the existing social order, and the oppositional role of the 'ulama' in political life was perhaps even further diluted. Yet at the same time, the autonomy of the 'ulamā' and the whole Sharʿī system from the military rulers, the amīrs, was given a definitive form.”[7] [emphasis added]

An immense opportunity lies in front of those involved in our modern madrasahs: we may work together to establish strong networks that can resist the ever-changing political tide, or remain disunited, like lone sheep that can be easily picked off.

Part of the solution lies in learning from these examples of the past. We must study our history, not to romanticize it, but to avoid repeating its mistakes. We must plan carefully, teach sincerely, and remind ourselves that those who do not know their history have no future. As we work with the asbāb present before us, we also remember that only Allah guides and decides whether these institutions last or perish.

قُلْ إِنَّ ٱلْهُدَىٰ هُدَى ٱللَّهِ

“Say: Indeed, [true] guidance is the guidance of Allah.” (Sūrah Āl ʿImrān, 3:73)

May Allah protect our madāris, our masājid, and our scholars. May He fill our institutions with sincere hearts and inquisitive minds. And may He return Madrasah Ibn Yūsuf and places like it to their rightful place as sanctuaries of truth. Āmīn.

والحمد لله رب العالمين

Notes

[1] Ibn Baṭṭūṭah, Riḥlah Ibn Baṭṭūṭah (Dār al-Sharq al-ʿArabī), 2:522.

[2] Al-Ḥasan b. al-Wazzān al-Zayyātī, Waṣf Ifrīqiyah, (Riyadh: Jāmiʿat al-Imām Muḥammad ibn Saʿūd al-Islamiyyah, 1979) 139.

[3] Ibn Kathīr, al-Bidāyah wal-Nihāyah (Dār al-Hajr, 1999) 11:693.

[4] Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifah). Murtaḍā Al-Zabīdī explains in his commentary on the Iḥyāʾ that “Ṭāhir” here refers to ʿAbd-Allāh b. Ṭāhir b. Ḥusayn, an Abbasid governor who was known to wear extravagant clothing. See Itḥāf al-Sādah al-Muttaqīn (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah), 1:586.

[5] Ibn al-Hājj Al-Fāsī, Al-Madkhal (Dār al-Turāth), 1:134-135.

[6] Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Concept of Education in Islam: A Framework for an Islamic Philosophy of Education (Kuala Lumpur: ISTAC, 1999), 33-34.

[7] Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam Vol. 2 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974), 47-48.

Mufti Hussain Kamani is the Director of the Qalam Seminary and a senior faculty member, where he teaches hadith, fiqh, and tazkiyah. With over two decades of experience in teaching and community leadership, he has mentored and trained over a thousand students, many of whom now serve as imams, chaplains, educators, and leaders across the United States.