Morocco: Pages of a Living Tradition | Pt. III

Mufti Hussain Kamani

This is part III of a travelogue series. Click to read part I and part II.

Part III: Rabat & Fes

After exploring Marrakesh on our own, we united with the rest of our Qalam Hadith Tour group in Casablanca and proceeded to visit Rabat and Fes, both of which will be detailed in this travelogue. From Casablanca we journeyed along the Atlantic coast toward Rabat, Morocco’s capital. The drive took just over an hour and a half.

Our day began at the Qasbah of the Udayas (قصبة الأوداية), perched above the Bou Regreg River, facing the neighboring city of Salé (سلا). Originally established by the Almohads in the 12th century, its layout is a fascinating study in Islamic urban planning. The homes have thick outer walls and open into sunlit courtyards. Narrow alleys restrict movement for potential invaders. Every design element reflects a commitment to privacy. Windows do not face other windows, and doors of opposite houses never align. As our guide beautifully put it: “In our tradition, even architecture guards ḥayāʾ (modesty).”

From there we walked to the Hassan Mosque, the grand but unfinished vision of Sultan Yaʿqūb al-Manṣūr (r. 1184–1199). Towering above us stood the Hassan Minaret (صومعة حسان), part of what was once intended to be the largest mosque in the western Islamic world. We prayed ẓuhr among the forest of stone columns under the open sky.

Rabat was once known as Ribāṭ al-Fatḥ — “The Fortress of Victory” — a strategic hub for launching military campaigns toward al-Andalus during the Almohad period. But after al-Mansur’s death in 1199, the grand project of the capital came to a halt. By the 16th century, Rabat had declined so severely that only about a hundred houses remained inhabited.

Its revival followed tragedy and migration. In 1609, King Philip III expelled the Muslims and Jews from Spain. About 13,000 of these exiles settled in Rabat, revitalizing the city with new life and a strong Arab-Andalusian identity.

After finishing our prayers, we returned to our bus and shortly thereafter experienced a minor accident. Another vehicle had rear-ended us, though most passengers barely noticed the impact. The official report process nonetheless took nearly an hour and a half; we made use of our time on the bus to catch up with the group members and observe the bustling city around us. Eventually, we made our way to a Moroccan restaurant for lunch and enjoyed a relaxed, traditional meal.

One detail worth noting is how almost all mosques in Morocco are exclusively open to Muslims. This policy, which may surprise some travelers, is rooted in the post-colonial assertion of Moroccan Islamic identity; it was a defensive response to the French protectorate era, during which many religious lines were blurred or outright attacked. Now, the boundaries are clear and respected.

By mid-afternoon, we began our journey to Fes, leaving behind a city that quietly commands reflection. Rabat is not a city of spectacle, but it is full of symbolism. A city once nearly lost now stands firm as the heart of a nation.

Fes

After arriving in Fes, we ended the day with a gathering in which we began our study of Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ’s al-Shifā.

We opened the evening by reflecting on the historical role of hadith in our religion and the unique robustness of the sciences of Islam. The preservation of the Quran and sunnah is nothing short of a miracle, protected by generations of meticulous scholarship.

We then had a very meaningful discussion about the authority of the Prophetic tradition in the life of a Muslim. We invited attendees to share any doubts they may have carried silently, or criticisms they’ve heard over the years. What followed was a rich and honest exchange. The students raised thoughtful questions and we were able to address many of their concerns.

What made the session so beautiful was the students themselves: their openness, sincerity, and eagerness to learn created an atmosphere of trust and growth. It was clear they were not only listening but actually absorbing what was being shared.

We concluded by studying al-ḥadīth al-musalsal bil-awwaliyyah, also known as ḥadīth al-raḥmah, as a way to participate in this living tradition. A ‘ḥadīth musalsal’ is a type of narration that is transmitted in the same manner by every narrator in the sanad (chain of transmission), and this particular one has been traditionally taught as the first hadith a teacher ever transmits to his students. This narration is a deeply profound way to inaugurate the teacher-student relationship, as in it the Prophet ﷺ says:

الرَّاحِمُونَ يَرْحَمُهُم الرَّحْمَنُ، ارْحَمُوا مَنْ فِي الأَرْضِ يَرْحَمكُمْ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاءِ.

The merciful will be shown mercy by al-Raḥmān (the Most Merciful). Be merciful to those on the earth, and the One in the heavens will be merciful to you. [Sunan Abī Dāwūd & Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī]

Mufti Muntasir then shared a unique sanad for this very hadith, valued for how short it is. He personally received this chain right here in Morocco from Shaykh al-Kattānī, one of the most renowned contemporary scholars of hadith, before the shaykh’s passing رحمه اللّه.

The History of Fes

From the moment I entered this city I felt its weight, not just in the architecture or historical sites, but in the unseen spiritual presence that courses through it. This is a city long associated with sanctity. I had yearned to visit for years due to its frequent mention in classical Islamic texts and the number of scholars who either hailed from here or were drawn to it.

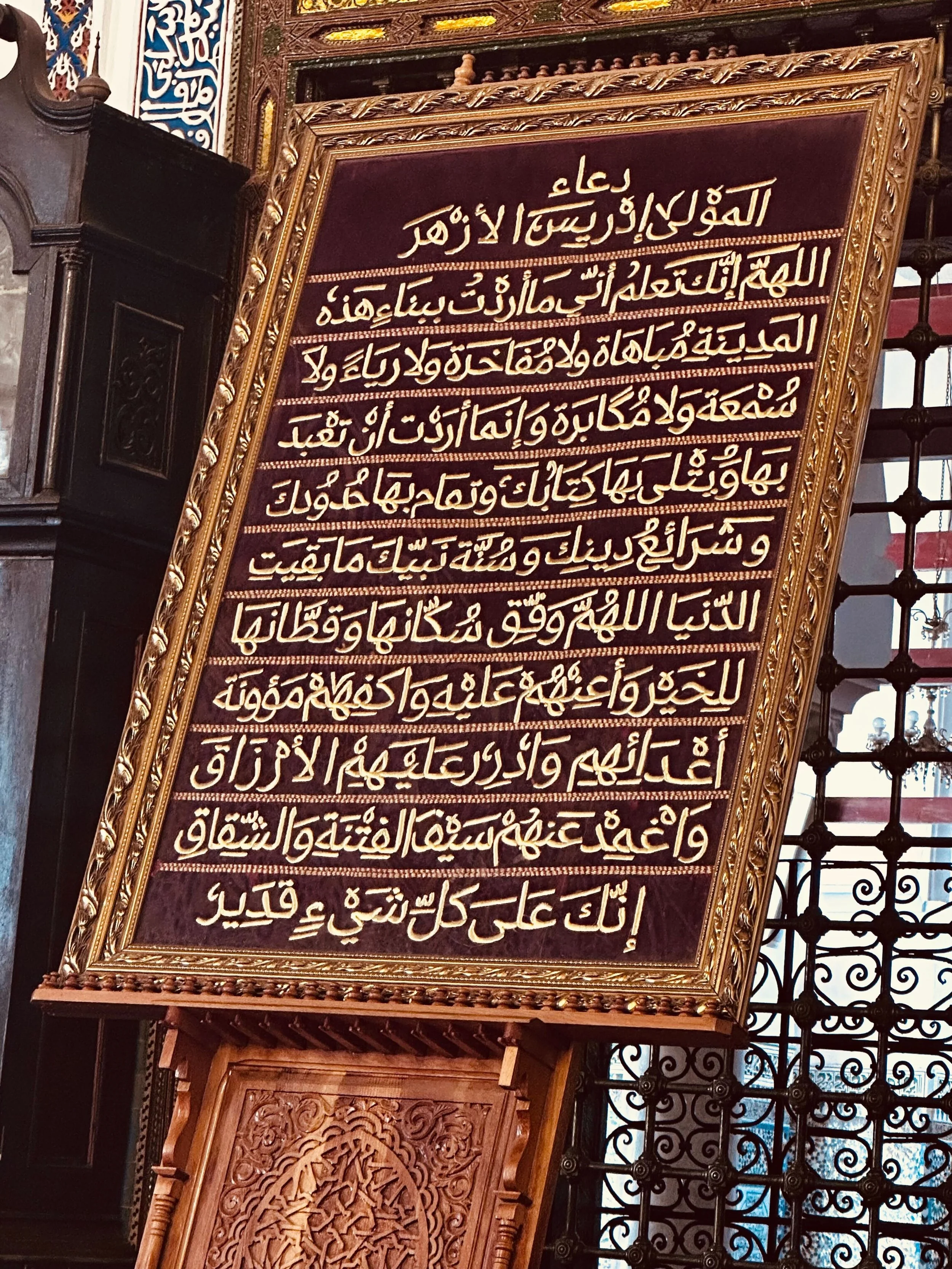

One of my most meaningful moments came when I stood at the maqām (tomb) of Moulay Idris II, the city’s founder and a descendant of Rasūl-Allāh ﷺ. Mufti Muntasir and I paused in quiet awe, reflecting on the light of ahl al-bayt and the barakah that emanates from this land. Moulay Idris made a heartfelt duʿāʾ for Fes upon founding the city:

اللهم إنك تعلم أني ما أردت ببناء هذه المدينة مباهاة ولا مفاخرة ولا سمعة ولا مكابرة، وإنما أردت أن تعبد فيها، ويتلى بها كتابك، وتقام بها حدودك وشرائع دينك وسنة نبيك محمد صلى الله عليه وسلم ما بقيت الدنيا…[1]

O' Allah! You know that I have not built this city for vanity, pride, renown, or arrogance, and I have only wished that You be worshipped in it, that Your Book be recited in it, that Your laws and sharīʿah be upheld and the sunnah of Your Prophet ﷺ be observed, for as long as this world remains.

Fes has a unique topography, and those who built the city employed fascinating techniques in urban engineering. The medieval geographer Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī marveled at its location. He writes:

وفاس مختطّة بين ثنيّتين عظيمتين وقد تصاعدت العمارة في جنبيها على الجبل حتى بلغت مستواها من رأسه وقد تفجّرت كلها عيونا تسيل إلى قرارة واديها.[2]

Fes was laid out between two great mountains, and its buildings rise up the sides of the mountain until they reach nearly to its summit. The entire area has burst forth with springs that flow down into the basin of its valley.

Eight rivers fed by springs west of the city split and wind through Fes, powering 600 water mills that operate day and night. As a result, water flows into every home through private canals and water troughs, an astonishing engineering feat unmatched in the region.[3] The water system supported not only agriculture and homes but also an entire textile industry. Fes was historically famed for its crimson dyes and luxury fabrics. This helped establish it as a powerful economic hub.

Historians emphasize that Fes was not one city but two. The northern bank is known as ʿUdwah al-Qarawiyyīn, and the southern bank as ʿUdwah al-Andalūsiyyīn. These were settled respectively by migrants from Qayrawān and Andalus, each bringing their distinct cultures.

Each quarter had its own jāmiʿ masjid, scholars, and community life, and rivalries ran deep. Al-Idrīsī notes that conflict and bloodshed between the two sides were unfortunately frequent:

وبين المدينتين أبدا فتن ومقاتلات وبالجملة إن أهل مدينة فاس يقتل فتيانها بعضهم بعضا.[4]

There is intense conflict and violent clashes between the two cities. In sum, the youth of Fes shed the blood of their own.

Despite its infighting, Fes became a central meeting point in the Maghrib. As al-Idrīsī describes it:

ومدينة فاس قطب ومدار لمدن المغرب الأقصى…هي حضرتها الكبرى ومقصدها الأشهر وعليها تشد الركائب وإليها تقصد القوافل ويجلب إلى حضرتها كل غريبة من الثياب والبضائع والأمتعة الحسنة.[5]

The city of Fes is the pivot and axis of the Maghrib… It is the greatest capital (in the region) and its most renowned destination. To it mounts are girded, and toward it caravans set out. All sorts of rare fabrics and valuable goods are imported to it.

Fes's economic and scholarly renown made it the destination of traders and seekers of knowledge from far and wide. Students stayed in eleven residential madrasahs, including the famed madrasah of Sultan Abū ʿInān, or the Bou ʿInāniyyah. Teachers were well-compensated, and they taught disciplines across the Islamic and natural sciences.

Walking through Fes, I felt that its past was alive and well-preserved: in the layout of its madinah, in the crafts being made and sold in the markets, in the old mosques and quiet zawiyas, and in the scholarly legacy of places like al-Qarawiyyīn. Even the cobbled alleys and uneven steps seem to have refused modernity’s flattening pressure.

The word madīnah here doesn’t simply mean "city," but refers specifically to the walled-in residential areas and market, separated from the countryside that lies beyond. Within these walls is a labyrinth of over 9,000 alleys and streets.

At first, walking through the madinah was disorienting: narrow alleys with high-walled homes on both sides, sudden openings into courtyards or bustling market squares, and turn after turn lined with shops. But slowly, it all began to make sense. Each cluster of stalls was dedicated to a specific trade. Not only did we see leather shoes being sold, we got to see them being cut, stitched, and polished by hand. Men and women were dyeing wool in vibrant colors in the area where woven goods were sold.

One store we entered was a pharmacy, but not the kind with shelves of plastic bottles and fluorescent lighting. This one was devoted entirely to argan oil, with rows of beautifully arranged soaps, balms, perfumes, and herbal treatments. The shopkeeper explained the benefits of each product with pride, all locally made.

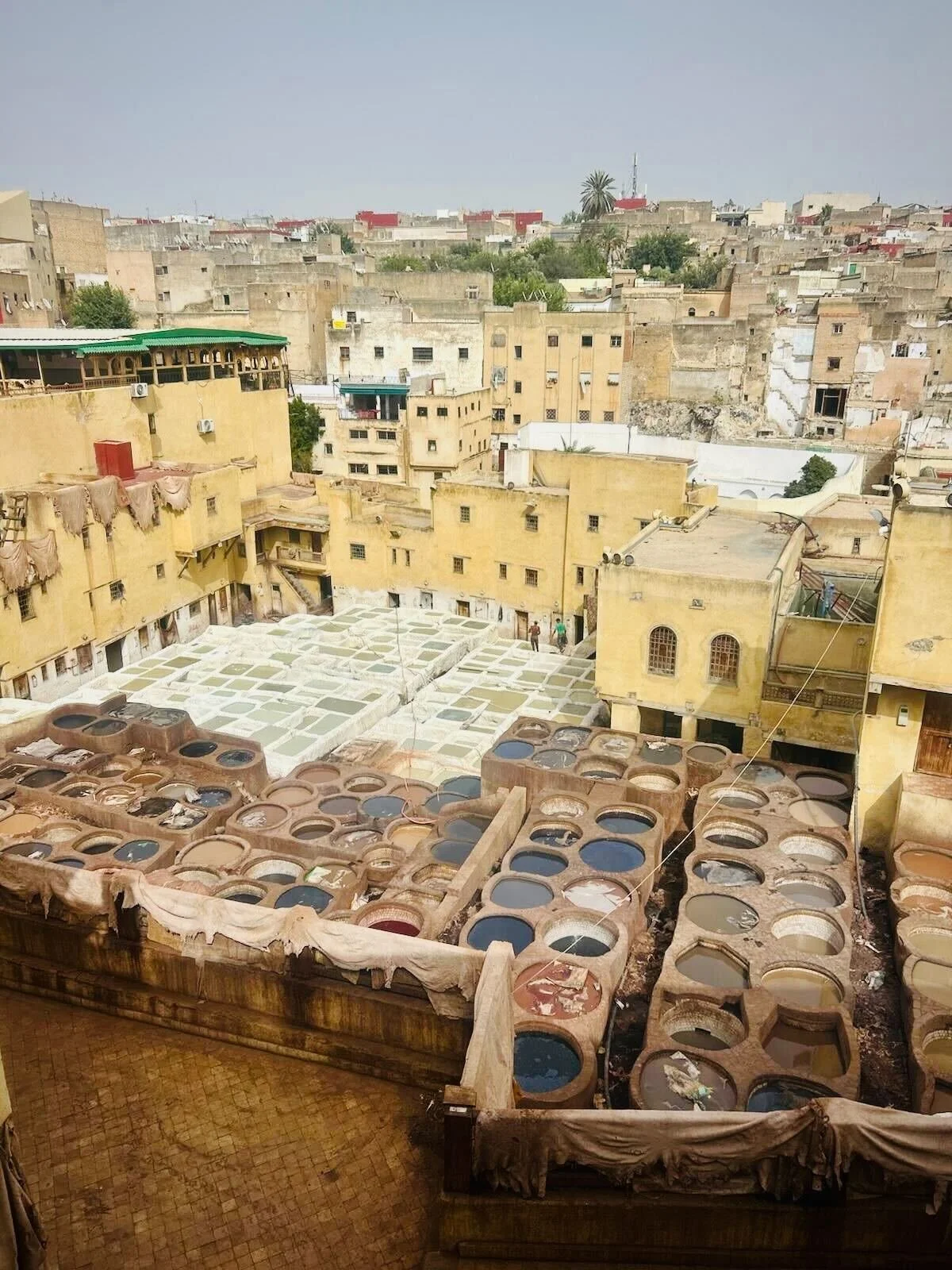

Nothing quite prepared us to walk through the tanneries. Our guide handed us each a small bunch of fresh mint leaves with a smile that suggested he knew what was coming. “Keep this near your nose,” he said. The scent became more and more pungent until we finally walked onto a balcony overlooking the Chouara Tannery, one of the oldest in Africa. From above, it was a mesmerizing sight: large circular stone vats filled with various shades of liquid, hides laid out like giant petals drying under the sun. The smell may have been overwhelming, but the preservation of this centuries-old craft was a sight worth seeing.

Further along in the market, we passed an area dedicated to fabric weaving, but not with silk or cotton. Here, artisans were producing textiles from cactus fiber, something I had never encountered before. The craftsmanship on display gave the madinah the feeling of a living museum, except that this is still their livelihood.

The people of the madinah work incredibly hard. With every passerby, they offer a pitch for their goods and urge you to enter their shop. They could spot a tourist from a hundred feet away, and yes, the prices do increase exponentially for foreigners. But we couldn’t help but laugh. It was all part of the experience. One could hardly blame them. Craftsmanship is a permissible and noble way to provide for one’s family, rooted in hard work and ancient trades.

What struck me most was how collaborative the atmosphere was. If a shopkeeper didn’t have your size or color, he’d call out across the alley to his friend. “Yusuf! Do you have this in brown?” And Yusuf would come jogging over, eager to help. Instead of being cutthroat competitors, they were like a family. This cooperative culture is rare in markets across the world, but here in Fes it seemed natural and sincere.

The markets of Fes revealed that this is not just a city of saints and scholars, but also craftspeople, traders, and families. There is something very special about a place where sincerity is not just preached but also practiced, whether in the masjid or the tannery.

Al-Qarawiyyin

Tucked in the heart of the madinah is Jāmiʿ al-Qarawiyyīn, which is regarded by many historians as the oldest continually operating university in the world. The masjid which eventually came to house a full-functioning madrasah was built in 245 AH / 859 CE by Fatima al-Fihriyyah, whose family had migrated to Morocco from Qayrawan, Tunisia.

When we entered the courtyard of the masjid to pray ẓuhr, we could barely walk barefoot on the tiles which lay under the scorching sun. We performed wuḍū’ from the iconic fountain in the center of the courtyard.

As the iqāmah was called, I was caught off guard for a moment. When the congregation stood for prayer, they didn’t face straight toward the wall in front of them and instead turned slightly to the left. I checked the compass on my phone, and the qiblah was indeed angled towards the corner of the masjid. After ṣalāh, Mufti Muntasir commented that when these masājid were constructed centuries ago, architects used the best methods available to determine the qiblah. But as more precise instruments were produced, it was discovered that the original direction was slightly off. You’ll find that many muṣallīs in Fes naturally adjust towards the true qiblah, sometimes even turning their backs slightly to the miḥrāb. It’s a small but profound symbol of how the pursuit of truth never stops, even after centuries.

Al-Qarawiyyīn and the neighboring madrasahs of Fes house a very rich intellectual history. Many renowned scholars once passed through these halls: Ibn Khaldūn, who composed parts of his Muqaddimah while living and teaching in Fes; al-Biṭrūjī, the Andalusian astronomer influenced by Ibn Rushd; and Ibn al-Ḥājj al-Fāsī, whose celebrated work al-Madkhal offered a scathing critique of religious corruption and innovation. Here taught Abū ʿImrān al-Fāsī, who helped cement the Mālikī madhhab as the dominant school in the Islamic west, especially through his impact on the Almoravid rulers. Here studied Ibn ʿAjībah, master of tafsīr and taṣawwuf and author of al-Baḥr al-Madīd.

Today, the doors of al-Qarawiyyīn are still open for students and its walls still echo with taḥmīd and takbīr. This masjid and madrasah is the beating heart of Fes, which has pulsed for over a thousand years.

Maqām Ahmad al-Tijānī

From there, we made our way to the resting place of Imām Aḥmad al-Tijānī (رحمه الله), the founder of the Tijāniyyah order, which is one of the most influential sufi tarīqahs in Africa. Born in ʿAyn Māḍī (present-day Algeria), he eventually made Fes his home.

His message was both traditional and radically simple: return to the Quran and Sunnah, adhere to the sharīʿah, and purify your heart. His teachings have reached the corners of Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, Mauritania, and beyond. Generations of scholars and laypeople alike have followed his waẓīfah (spiritual regimen).

In the shops outside the maqām, I was searching for a particular type of tasbīḥ I’d received a few months back. It was a gift from my colleague, Ustadh Omair. I showed the seller the one I had in my pocket, and he immediately smiled and said: "This one? I sold it to the person who gave it to you. I’m the only one who sells it here." We both laughed. Somehow a small tasbīḥ became a bridge between people who lived on opposite ends of the world and a reminder that Allah can weave hearts together through His worship.

That evening after returning to the hotel, we prayed maghrib together and gathered again for our nightly hadith session. The focus of our class was a powerful section from al-Shifā on the character of the Prophet ﷺ. Before opening the text, I posed a question to the attendees:

“If you were to meet the Prophet ﷺ, what aspect of his character do you think you would encounter?”

The responses were very heartwarming. Each person shared a different beautiful trait: his mercy, his smile, his patience, his attentiveness, his humility. It reminded us that the Prophet ﷺ wasn't just a distant figure in history. We all prayed that we would one day meet him ﷺ.

We then turned to the text. One passage stood out:

وَأَمَّا حُسْنُ عِشْرَتِهِ وَأَدَبِهِ وَبَسْطُ خُلُقِهِ ﷺ مَعَ أَصْنَافِ الْخَلْقِ...

As for his ﷺ fine companionship, refined manners, and expansive character with all kinds of people…

Then the narrations followed:

Jarīr b. ʿAbd-Allāh ؓ said: “Since I accepted Islam, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ never refused to meet me, and he never saw me except that he smiled.” [Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim]

Anas ؓ said: “If someone leaned close to the Prophet ﷺ to whisper, he would never pull his head away until the person himself did. No one ever held his hand except that he would not let go until the other person did. He never placed his knees ahead of a companion seated before him.”[6]

After reading these hadiths, the room fell into a deep silence. We weren’t just studying a text. We were studying the character and personality of Rasūl-Allāh ﷺ, the most beloved of creation to Allah.

We spent time reflecting together on how we could adopt aspects of Prophetic character in our own lives. The attendees spoke of patience with family, greeting others first, listening attentively, and never letting go of someone’s hand — both literally and emotionally — before they let go of ours.

At the end of the session, I reminded everyone that even though we didn’t live with the Prophet ﷺ in this world, we will inshāʾAllāh see him in the next. And when we do, we won’t just behold his blessed face; we will drink from the sweet cup of kawthar and witness his beautiful character firsthand. The Prophet ﷺ is not behind us. He is ahead of us, waiting.

That night, the room emptied very slowly. People lingered, not just out of courtesy, but out of love. For a brief moment, we all saw a glimpse of how it felt to be in the presence of the Prophet ﷺ.

Visiting Qāḍī Abū Bakr b. al-ʿArabī (رحمه الله)

Before we left Fes the next morning, we made one final stop to the grave of Qāḍī Abū Bakr b. al-ʿArabī al-Mālikī (468–543 AH / 1076–1148 CE), one of Andalusia’s most brilliant scholars. From his birth in Seville to his long travels through Baghdad, Damascus, al-Quds, Egypt, and the Hijaz, Ibn al-ʿArabī was a true seeker of knowledge. One of his most impactful teachers was Imām Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī. He later recorded this legendary scholarly journey in his work, Tartīb al-Riḥlah lil-Targhīb fī al-Millah.

Ibn al-ʿArabī’s intellectual journey actually began with his father, who was also a great scholar. He said:

صحبت ابن حزم سبعة أعوام، وسمعت منه جميع مصنفاته، سوى المجلد الأخير من كتاب الفِصَل، وقرأنا من كتاب الإيصال له أربعة مجلدات، ولم يفتني شيء من تواليفه سوى هذا.

I accompanied Ibn Ḥazm for seven years and heard all his works from him except for the final volume of al-Fiṣal. We read four volumes of al-Īṣāl with him, and I missed nothing else of his writing.[7]

Imām al-Dhahabī wrote regarding Ibn al-ʿArabī:

أدخل الأندلس إسنادًا عاليًا وعلمًا جمًّا، وكان ثاقب الذهن عذب المنطق كريم الشمائل كامل السؤدد. [..] وكان القاضي ممن يقال إنه بلغ رتبة الاجتهاد.[8]

He brought into al-Andalus high chains of transmission and abundant knowledge. He had a sharp intellect, eloquence, noble character, and perfect dignity. [..] It was said that he reached the level of ijtihād.

Among his most widely referenced works are his sharḥ of Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī and his Aḥkām al-Qurʾān. As al-Ḥajjārī said:

لو لم يُنسب لإشبيلية إلا هذا الإِمام الجليل لكان لها به من الفخر ما يرجع عنه الطرف وهو كليل.[9]

If Seville had produced no one but this noble Imam, it would suffice as a source of everlasting pride.

Despite coming from a wealthy family, Ibn al-ʿArabī dedicated his life to study, teaching, and writing. When removed from his judicial post, he didn’t retreat in resentment. Instead, he continued his mission as a seeker, a teacher, and a servant of this dīn. He died in Rabīʿ al-Ākhir 543 AH / 1148 CE in Fes. Standing by his grave, I was reminded that the legacy of scholars is not written on their tombstones. It’s written in hearts they move, the students they raise, and the books they leave behind. اللهم ارحمه، واجعلنا من ورثة هذا الدين بعلم وإخلاص، لا بكلام فقط

Fes was the home and burial place of countless other renowned scholars as well. Ibn Ājurrūm, the famous grammarian and author of one of the most widely studied naḥw texts, is buried in the Andalūsī quarter of Fes. Unfortunately we were not able to visit his grave on this trip. With the permission of Allah, in future travelogues I will share details from the remaining cities we visited: Chefchaouen and Tangier.

والحمد لله رب العالمين

Notes

[1] Aḥmad al-Nāṣirī, Al-Istiqṣā li-Akhbār Duwal al-Maghrib al-Aqṣā (Casablanca: Dār al-Kitāb 1997), 1:223.

[2] Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī, Muʿjam al-buldān (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1995), 4:230.

[3] Muʿjam al-buldān, 4:230; al-Ḥamawī writes: وليس بالمغرب مدينة يتخللها الماء غيرها إلا غرناطة بالأندلس.

[4] Muḥammad al-Sharīf al-Idrīsī, Nuzhah al-mushtāq fi ikhtirāq al-āfāq (Beirut: ʿĀlam al-Kutub, 1989), 1:242.

[5] Al-Idrīsī, 1:246.

[6] Here it seems that Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ combined the mutūn of multiple narrations and presented them as one continuous narration from Anas. The different parts of the narration are found in Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī and Sunan Abī Dāwūd.

[7] Al-Dhahabī, Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ (Muʾassasah al-Risālah, 1985), 20:201.

[8] Al-Dhahabī, Siyar, 20:200.

[9] Ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī, Al-Mughrib fī Ḥulā al-Maghrib (Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif, 1955), 1:254.

Mufti Hussain Kamani is the Director of the Qalam Seminary and a senior faculty member, where he teaches hadith, fiqh, and tazkiyah. With over two decades of experience in teaching and community leadership, he has mentored and trained over a thousand students, many of whom now serve as imams, chaplains, educators, and leaders across the United States.