A Research-Based FAQ for Students of Arabic

Ustadh Syed Omair

While ṭullāb al-ʿilm are not a homogenous group, there are common questions that arise regarding the process of ṭalab al-ʿilm: the act of seeking sacred knowledge. Much of this advice ends up being repeated, and yet much of it ends up being forgotten by students at various levels. The following article aims to catalog and address some of the most common questions posited by ṭullāb al-ʿilm, and particularly those related to the acquisition of the Arabic language, which is the main subject of study for the first year of the five-year Qalam Seminary program. This article is part of an ongoing series about learning Arabic, aiming to prepare students for the long but rewarding journey of studying the language of the Quran.

How do I improve my Arabic?

This is perhaps the most common and most open-ended question that is asked, and there really is no single answer since each student is at a different stage in their own Arabic journey. Teachers will give slightly different answers to this question, but there are some general issues that we can focus on to help students improve their overall Arabic, not all of which will apply to each student.

The first issue is reading fluency. What many students perceive as weakness in Arabic is really a lack of confidence in their overall reading ability, letter pronunciation, and connections between words in reading. The way to improve this is to work on one’s tajwīd, the rules governing Quranic recitation, and to engage in munāẓarah, or reading one-on-one with another person.

One may ask how studying Quranic recitation will help in other subjects, but it should be noted that reading, recognizing words, and having confidence in one’s pronunciation are skills that transfer to all disciplines. A student can possess an incredible amount of knowledge, but if they feel too timid to share with others or read to their teacher, the teacher will assume they simply lack knowledge of Arabic. Therefore, a deliberate approach must be taken to build up one’s confidence through repetitive practice.

The second issue is breadth of vocabulary. A teacher of mine once shared a good rule of thumb: take the amount of vocabulary you know and multiply it by ten, and then you’ll be ready to engage most Arabic texts. While this statement may seem hyperbolic, it contains a good deal of truth. Students often vastly overestimate the importance of grammar, and conversely vastly underestimate the importance of building a large repository of general and specialized vocabulary. Many students have experienced knowing the grammatical function of every single word in a sentence, but having no idea what the sentence means. That is because grammar does not encompass language, though it is a necessary component. The more one expands their Arabic vocabulary, the more their comprehension and confidence typically increase. In an article on language skills and vocabulary in the Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, Alaa Alahmadi and Anouschka Foltz state:

Various researchers have noted the influence of lexical knowledge on the four language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing). Most of these studies focus on reading skills (e.g. Laufer 1992; Ouellette 2006; Qian 1999, 2002). Schmitt et al. (2011, p. 39) argue that “there is a fairly straightforward linear relationship between growth in vocabulary knowledge for a text and comprehension of that text”. In line with this, Stæhr (2008) found a stronger relationship between vocabulary size and reading skills than vocabulary size and writing or listening skills…

In line with such results, some researchers have proposed a minimum level of vocabulary size needed for certain language tasks. Milton (2009), for instance, suggested a vocabulary size of 3000 words to successfully engage in a simple conversation. Laufer (1989) proposed a threshold of 5000 word families for an average of 95% text coverage for academic texts. Similarly, Laufer and Ravenhorst-Kalovski (2010) and Nation (2006) proposed a level of 8000 word families for 98% text coverage for a variety of authentic texts.[1]

For reference, the Quranic text has 14,870 unique words, not counting repeated words.[2] Note that this should not be confused with word families, which are broader than single words. In light of this, a student knowing only 1,000 to 2,000 unique words will most certainly struggle to understand the words of the Quran. The vocabulary of the hadith corpus likely dwarfs this number. It is therefore imperative for students to dedicate daily time to acquiring more vocabulary in a systematic way.

The final issue to be addressed in this article is knowledge of Arabic grammar, which revolves around the two disciplines of ṣarf (morphology) and naḥw (syntax). Of these two disciplines, ṣarf, or the study of word forms, is the logical foundation, since naḥw is the study of sentence building, and sentences, of course, are composed of words. These disciplines must be approached systematically and studied in-depth at a steady pace, not at the expense of reading Arabic texts, but as a necessary accompaniment, in tandem with improving fluency and acquisition of vocabulary.

To demonstrate one common issue: in many Arabic language institutes in the West, ṣarf is often given a backseat to naḥw, which is treated as the be-all and end-all of Arabic study. Students then struggle when coming across irregular verb and noun patterns, emphatic phenomena such as nūn al-tawkīd, forms beyond the common “Ten Forms”, and other situations. This often goes unaddressed, leaving students confused and frustrated. In reality, a strong grasp of both naḥw and ṣarf is required before taking on intermediate and advanced Arabic texts of the various Islamic disciplines, as opposed to texts written for language acquisition, which may avoid complicated irregular vocabulary and linguistic constructs.

It is important to note, once again, that knowledge of grammar does not necessarily translate into better comprehension of texts, but it does allow students to more clearly understand the authorial intent of a text and helps them gain access to highly advanced texts such as the Quran and the hadith literature. Many students focus exclusively on studying grammar and miss the forest for the trees, wondering why they cannot comprehend even basic or intermediate level texts. A balanced approach to grammar and skills application should be utilized by students.

How do I memorize the huge amount of information that I am expected to memorize?

This is another common question, and the answer will differ from student to student since no two people memorize the same way. Here is a quick and convoluted survey of techniques, just to give an idea of what is mentioned in academic studies on memorization:

There are multiple memorization techniques. For example, some authors suggest training memory by using images, images and rhymes, creating personal memorable associations, dividing words into significant parts, combining sentences to write or inventing stories [8]. Some Russian scholars suggest the use of “mnemotables'', which are schemes drawn with determined information, together with the following methods: "chain" (linking images in associations); symbolization (to memorize abstract concepts); tie concepts to familiar information to facilitate engagement [7]. Furthermore, it is appropriate to mention the technique of loci: the transformation of concepts, information, into mental images with the consequent positioning of these in places. This technique requires that the mental images created are clear and precise, in such a way as to always allow double encoding, that is, as we have viewed the image from the term (Encoding or Viewing Phase), it will be possible, having seen the image, to trace the information to remember (Decoding or Verbalization Phase); the P.A.V. (Paradox, Action, Vivid), a technique that allows you to associate a paradox with a certain element, transforming this element into an action. Using this tool, it is possible to provoke a vivid emotion in the subconscious that produces a mental connection capable of activating the ability to memorize. The technique of phonetic conversion, a technique of memorizing numbers. It works by converting numbers into consonants and, by appropriately adding vowels, transforming them into words that can be remembered more easily than a series of numbers, particularly using other mnemonic rules (P.A.V. and loci technique). Finally, we have the ''Keyword method'' (Atkinson) which is the most used memory technique in the study of foreign languages.[3]

If this seems like a lot of confusing information, that’s because it is exactly that. The point of this is to show the broad scope of different methods that are available. A much more useful list may be found from the Learning Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The introduction to their web page entitled Memorization Strategies states the following:

Many college courses require you to memorize mass amounts of information. Memorizing for one class can be difficult, but it can be even more frustrating when you have multiple classes. Many students feel like they simply do not have strong memory skills. Fortunately, though, memorizing is not just for an elite group of people born with the right skills—anyone can train and develop their memorizing abilities.

Competitive memorizers claim that practicing visualization techniques and using memory tricks enable them to remember large chunks of information quickly. Research shows that students who use memory tricks perform better than those who do not. Memory tricks help you expand your working memory and access long term memory. These techniques can also enable you to remember some concepts for years or even for life. Finally, memory tricks like these lead to understanding and higher order thinking. Keep reading for an introduction to effective memorization techniques that will help you in school.[4]

The key takeaway from this is that memorization is a skill, which the webpage calls a “technique” or “trick”, that can be developed and honed. What memorization is not is a random and unintended effect of proximity and vocal osmosis that occurs from sitting in a classroom and listening to a teacher, as many people unfortunately expect. Expecting to memorize vast amounts of information without investing the requisite effort is about as realistic as putting a list of vocabulary under one’s pillow and expecting it to be absorbed into the mind overnight.

All jokes aside, the point is that memorization is an acquired yet personalized skill. This means that part of the process is figuring out what your unique memorization style is. It may be as simple as repeating lists orally, writing out lists on paper, using flash cards, creating mnemonic devices, using word-picture association, a combination of the above, or something else entirely. There is no one technique that works for everyone and that is okay because no two people learn exactly the same way. Therefore, if you’re a student asking this question there is probably a technique that works for you and that you haven’t discovered yet, but you have the freedom to explore and figure it out yourself.

Why does it take so long to learn Arabic?

There are several aspects to this particular issue. The first is that, oftentimes, students have an expectation that everything they study should be extremely simple and easy to digest. This is not the case in almost any advanced academic subject, but for some reason it becomes a latent expectation in topics related to Islam — a projection that Islamic topics must be simple and immediately accessible.

The reality is that classical Arabic is a very nuanced discipline much more akin to an art form than just data and information. Yes, there is a component of Arabic that is very mathematical, particularly Arabic morphology and syntax to an extent, but the style and aesthetics of a particular author or speaker can take on myriad forms. Just as some people are more blunt and others more artistic when they speak, so too are their styles of writing. Expecting everyone to speak the exact same way is unrealistic in any language, and thus a projection of a firm set of rules and modes onto every Arabic speaker is unfair.

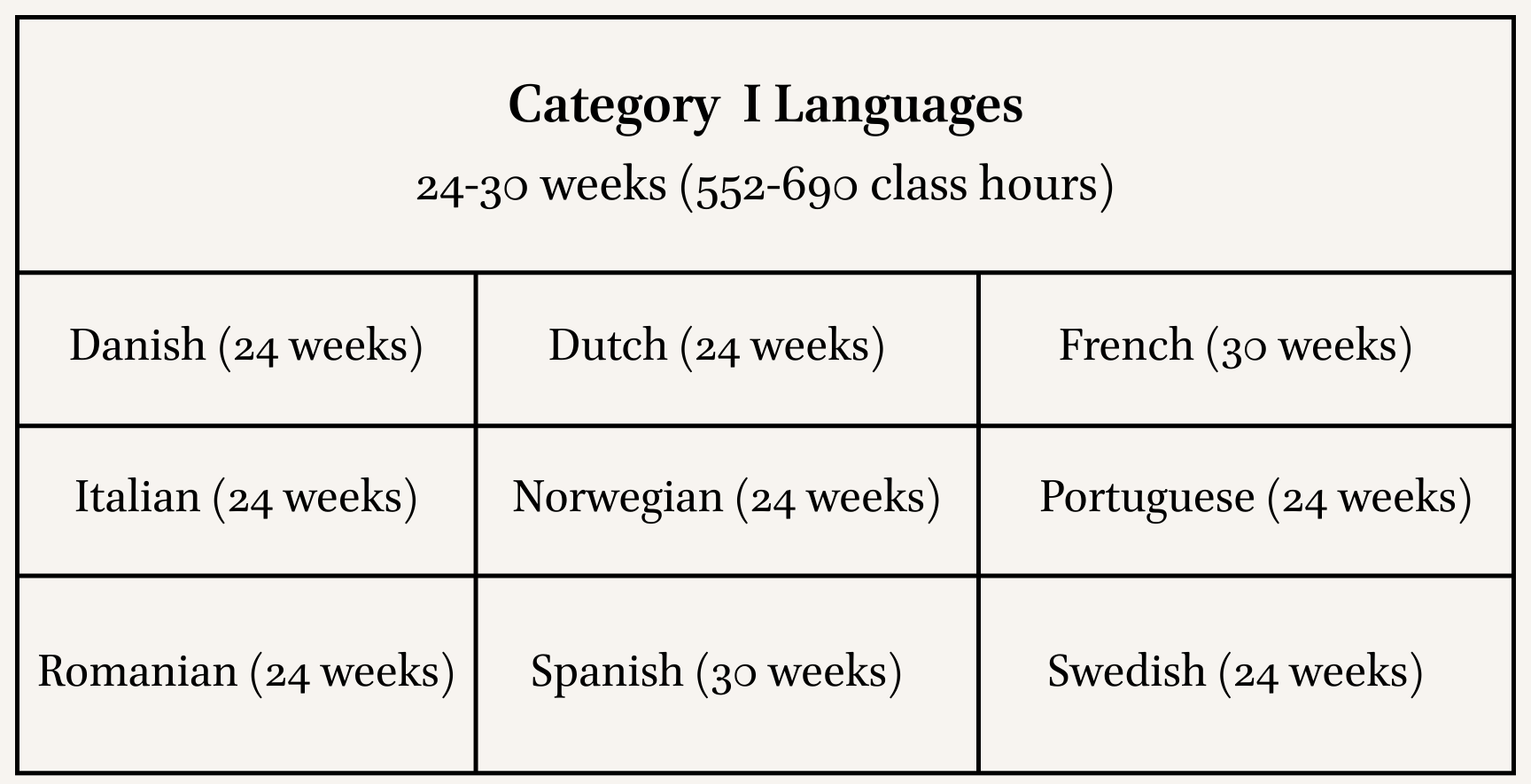

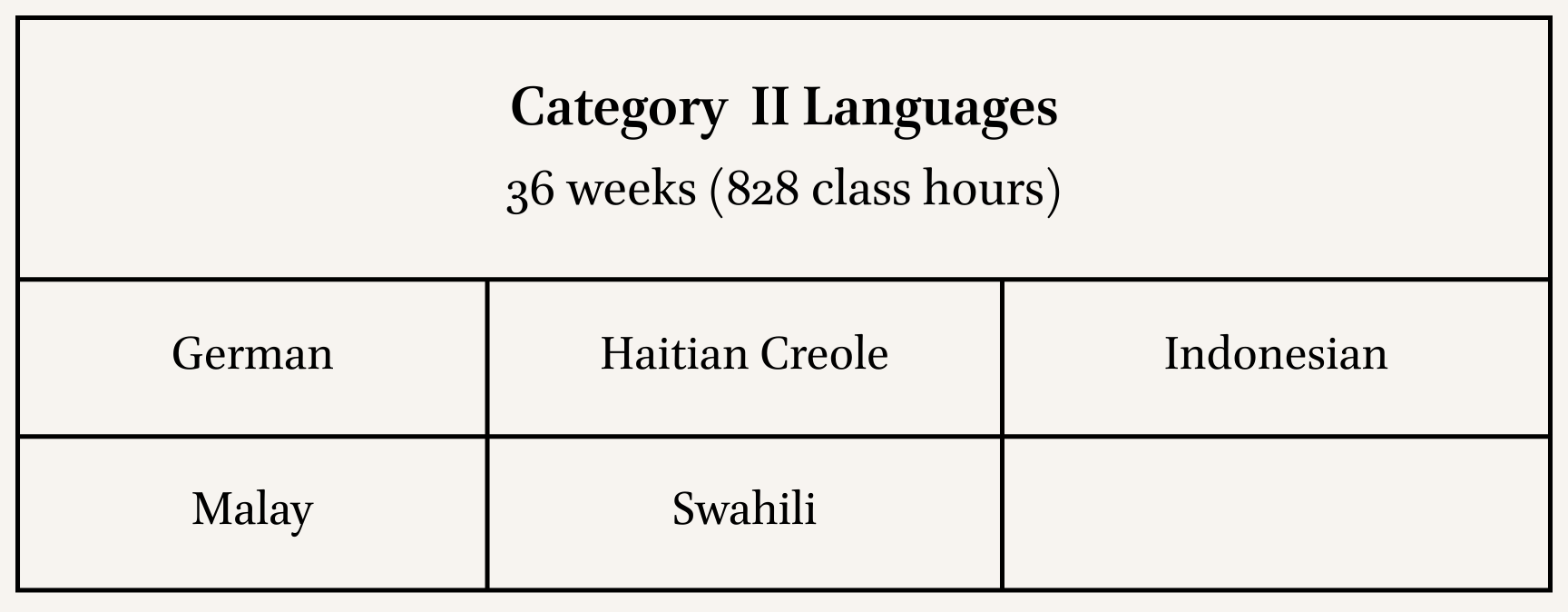

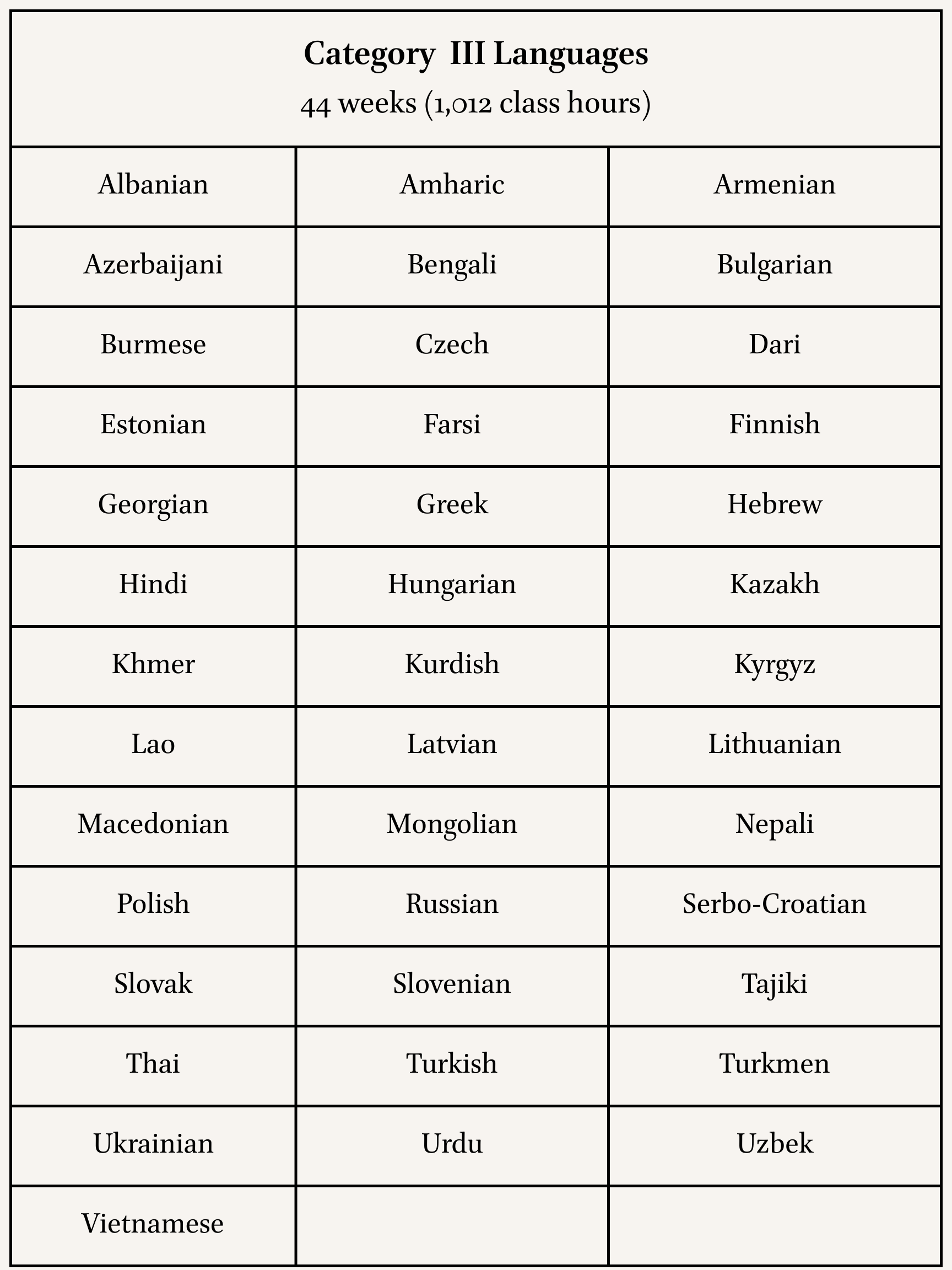

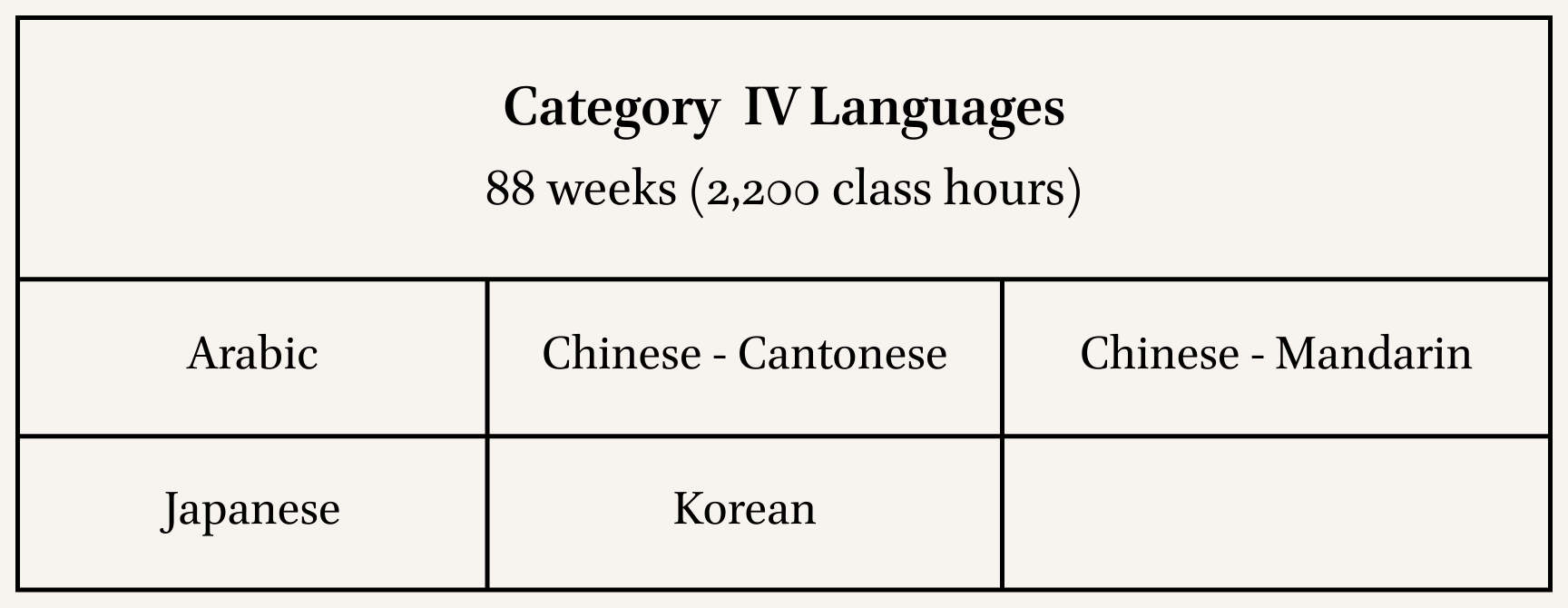

The second point to note is that Arabic is drastically different from English. In fact, they are not in the same or even adjacent language families. The National Foreign Affairs Training Center, a division of the U.S. Department of State, has developed an average time to reach “Professional Working Proficiency” on the International Language Roundtable grading scale. Professional working proficiency is defined as achieving an average score of three out of five total points, with a score of five indicating native or bilingual fluency. Below is the chart of languages and the approximate average time it takes to reach professional working proficiency, based upon a typical week of 23 hours of class and 17 hours of self-study.[5] See if you can spot where Arabic is.

As one can see, Arabic is considered one of the hardest languages to learn for English speakers. It’s worth mentioning that this is the case for Modern Arabic, and only in terms of speaking and listening. Given those parameters, it would take almost a year and a half of full time study to reach professional working proficiency. If we extrapolate this to Classical Arabic, which has an even broader scope of vocabulary, more stringent grammar, and a broad range of literary and poetic forms, it should become clear that learning, let alone mastering, Classical Arabic is a huge undertaking. We have spoken about this in a previous article.

Therefore, realistic expectations are necessary for a student undertaking the journey of learning Classical Arabic. Concepts may have to be reviewed several times before they sink in. In addition, higher forms of learning should be sought out, as may be referenced in well-known paradigms such as Bloom’s Taxonomy. Unlike higher learning forms, memorizing and regurgitating information do not demonstrate mastery; in fact, these skills are considered quite low in terms of demonstrating understanding of a concept. Rather, being able to manipulate, synthesize, and produce original examples of something leads to a much firmer understanding of the topic. In sum: there are no shortcuts or hacks to master Arabic. It simply takes time, serious study, revision, practice, and good instruction.

Notes

[1] Alahmadi, A. and Foltz, A. (2020) Effects of language skills and strategy use on vocabulary learning through lexical translation and inferencing, Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7661419/ (Accessed: 22 September 2025).

[2] Quran Statistics | Quran Analysis. Available at: https://www.qurananalysis.com/analysis/basic-statistics.php (Accessed: 22 September 2025).

[3] Ciaramella, F., Lorè, E.A. and Rega, A. (2020) Memorization techniques: a literature review to verify the feasibility of implementing memorization techniques through tangible user interfaces, Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Psychology-Based Technologies (PSYCHOBIT 2020). Available at: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2730/paper29.pdf (Accessed: 22 September 2025).

[4] Memorization Strategies. The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/enhancing-your-memory/ (Accessed: 22 September 2025).

[5] Foreign Language Training, U.S. Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/foreign-service-institute/foreign-language-training (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

[6] Note that Category III languages are designated as “Hard” languages. The webpage states that these are “Languages with significant linguistic and/or cultural differences from English.”

Ustadh Syed Omair serves as a faculty member at the Qalam Seminary. He earned a B.A. in Religious Studies from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. During university, he took a gap year to study at the Qasid Arabic Institute in Amman, Jordan, and after graduating from college he returned to Qasid as a teacher of Classical Arabic from 2010 to 2017. He taught all levels of the Qasid Curriculum while developing curriculum and textbooks as well. While in Jordan, he studied the Islamic Studies in private and evening classes, particularly focusing on Shafi’i fiqh, Aqidah, Hadith, and furthering his knowledge of the Arabic language. Since returning to the United States, he has taught for Fawakih Arabic Institute, served as an Imam at the ADAMS Center in Northern Virginia, and was an instructor at Islamic Foundation School in Villa Park, Illinois. He lives in Dallas with his wife and two children.